Why Does India Still Allow Politicians To Contest From More Than One Constituency?

18 April 2019 2:14 PM GMT

“One person, one vote” is the dictum that has been a founding principle of the world’s largest democracy, India. Besides its vastness and staggering diversity, Indian democracy is unique in that it began its journey with the element of universal suffrage, for all men and women, regardless of caste, religion, creed or wealth – unlike most other democracies that withheld suffrage from some classes of their citizenry for decades or centuries.

Elections are those festivals of democracy when once every few years voters exercise their most basic of rights to either reward the incumbent government with another term or usher in the winds of change by electing a new establishment. While they are not democracy in themselves, elections are probably the most important aspect of representative democracy, and how free and fair they are serves as a barometer to measure the health and progress of a nation’s democracy.

There are many kinds of elections in India – mainly, the general elections to elect the Parliament and the Assembly elections to elect the respective state Assemblies.

Elections in India are governed by the Representation of People’s Act, 1951 (RPA), and conducted and organised by the Election Commission of India (ECI).

Normally occurring once every five summers, the Indian general election season has always caught the world’s imagination. The weeks of relentless campaigning, all-or-nothing rhetoric, countless citizens braving the sun to listen to candidates’ pitches, the political maneuvering, the over-the-top press coverage, the larger-than-life election gimmicks – India’s elections are a spectacle like no other, the greatest show on earth.

The strange custom of candidates contesting from two constituencies

While India’s elections have always been the envy of the world for their regularity and relative fairness despite the size of the electorate and the vastness of the land itself, there are some areas where electoral reforms are still needed to make our elections more perfect and in tune to the needs of modern society.

One of these areas is the issue of candidates contesting from more than one constituency. As per Section 33(7) of the RPA, one candidate can contest from a maximum of two constituencies (more constituencies were allowed until 1996 when the RPA was amended to set the cap at two constituencies).

Since 1951, many politicians have used this factor to contest from more than one seat – sometimes to divide the opponent’s vote, sometimes to profess their party’s power across the country, sometimes to cause a ripple effect in the region surrounding the constituencies in favour of the candidate’s party.

And all parties have exploited Section 33(7). In 1957, a young Atal Bihari Vajpayee contested the Lok Sabha election from three different constituencies in Uttar Pradesh. Four decades later, when Sonia Gandhi, Vajpayee’s arch-rival, contested the Parliamentary election, she would do so from two corners of India – Amethi in UP and Bellary in Karnataka.

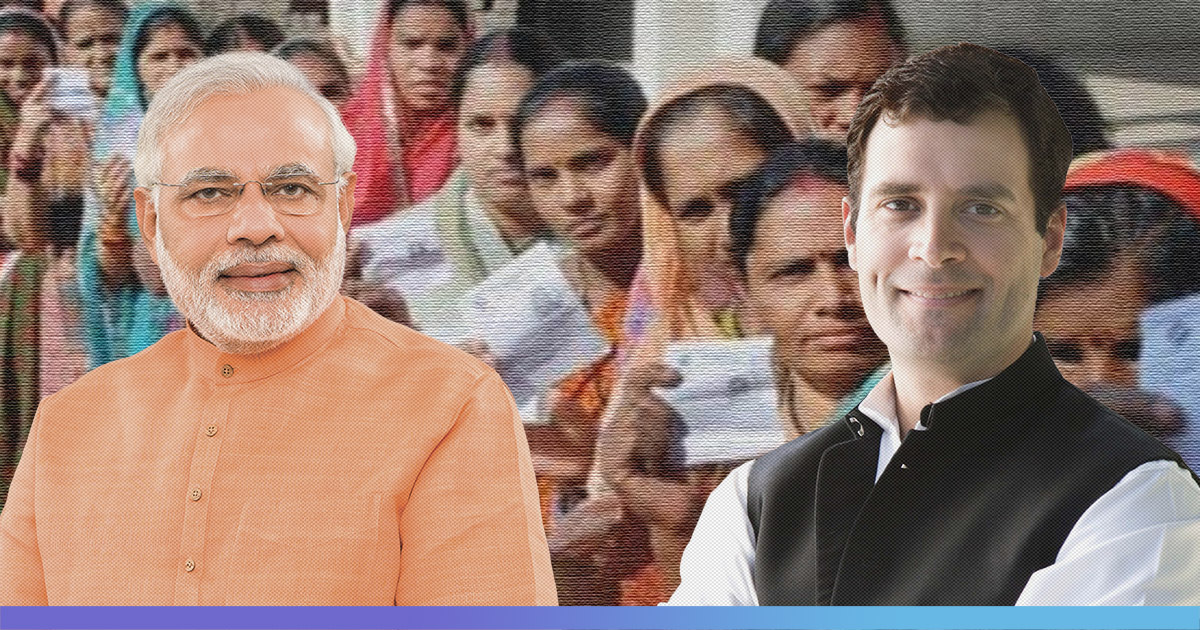

Similarly, five years ago Prime Minister Narendra Modi won the election from the seats of Vadodara and Varanasi. And this time around, Congress President Rahul Gandhi will reportedly contest the 2019 election from Wayanad, Kerala in addition to his family’s bastion in Amethi.

Why is this a problem?

The problem with allowing candidates to contest more than one seat is multifold.

Primarily, the problem with this system is that it is illogical – because while a candidate can contest from two constituencies in an election, no candidate can represent two constituencies in Parliament or a state Assembly.

The irony behind Section 33(7) of the RPA is that it leads to a situation where it would be negated by another section of the same Act – specifically, Section 70. While 33(7) allows candidates to contest from two seats, Section 70 bars candidates from representing two constituencies in the Lok Sabha/state Assembly.

This means that if a candidate contests from two seats and won both those seats, he or she is legally mandated to vacate one of the seats in favour of the other. This means that in the other constituency, a by-election would be automatically triggered – that too, immediately after the general election. For example, in 2014, after PM Modi won both Vadodara and Varanasi, he vacated his seat in Vadodara, forcing a by-election there.

Any candidate who contests from two constituencies knows that if he/she wins both constituencies, he/she will have to sacrifice one of the seats and trigger another election in that constituency – an election caused solely because of the RPA’s inconsistencies, an election that had never been necessary in the first place.

It goes without saying that besides the logical inconsistency of the situation, the inevitable strain on the public exchequer is a serious concern. Lakhs of taxpayer rupees need to be shelled out because of a by-election that could have been easily avoided. Before 1994, when candidates could contest from even three seats, the financial burden was even heavier. In fact, N T Rama Rao contested the 1985 Andhra Pradesh Assembly election from three seats – Gudivada, Hindupur and Nalgonda – and won all of them. After Rao retained Hindupur, by-elections were held in the other two constituencies to fill the two seats that he could not have filled in the first place.

Then there is the aspect of voter fatigue. A candidate who wins from two seats has to vacate one of the seats within ten days, following which a by-election will be held. Why should voters be compelled to vote twice in the same election for the same seat within a span of a few days? Many voters travel from out of town to cast their vote, many take time off of work, many walk long distances.

Furthermore, repeated elections are not only unnecessary and costly, but they will also cause voters to lose interest in the electoral process. Invariably, the by-election would most likely see fewer voters turn out to vote when compared to the first election a few days earlier.

What is the stand of the EC & the government?

The Election Commission recommended amending Section 33(7) so as to allow one candidate to contest from only one seat. It did so in 2004, 2010, 2016 and again in 2018. These were recommendations given to the Executive and the Supreme Court. (If not an amendment, the EC opined that a system should be devised wherein if a candidate contested from two constituencies and won both, then he or she would bear the financial burden of conducting the subsequent by-election in one of the constituencies. The amount would be Rs 5 lakh for a Vidhan Sabha election and Rs 10 lakh for a Lok Sabha election.)

In its 255th report, the Law Commission seconded the EC’s recommendations to amend the Act, sparking further proposals by the EC to the SC on the issue of electoral reforms.

However, the RPA cannot be modified by the EC or the SC. It was passed by Parliament and can be amended only through Parliamentary process (unless the SC strikes down Section 33(7) as unconstitutional).

In 2018, when the SC sought the government’s response on amending Section 33(7), the government argued in favour of maintaining the status quo, citing the “wider choice to the polity as well as candidates” that the system of one candidate, two constituencies provides. The government contended that doing away with the provision could cause an infringement of the rights of the candidates contesting elections as well as curtail choice of candidates to the polity.

As things currently stand, Section 33(7) remains in force. Candidates continue to contest from more than one seat. And because Section 70 also remains in force, a victory of a candidate in two constituencies will precipitate immediate by-elections – elections that are unnecessary, expensive and wholly counter-productive.

The government’s arguments in favour of 33(7) are both unreasonable and candidate-centric. A candidate’s entitlement to a “wider choice” cannot trump a voter’s right to know who he or she is voting for – the right to know that the candidate being chosen will surely represent the voter if the candidate wins. Claims of giving more choice of candidates to the polity are nonsensical. 33(7) enables the advent of parachute candidates – non-indigenous politicians placed by parties in a constituency to prove a point and not to represent the electorate of that constituency.

“One person, one vote” is the dictum that has been a founding principle of Indian democracy. Perhaps it is time to modify and expand that principle to “One person, one vote; one candidate, one constituency”.

All section

All section