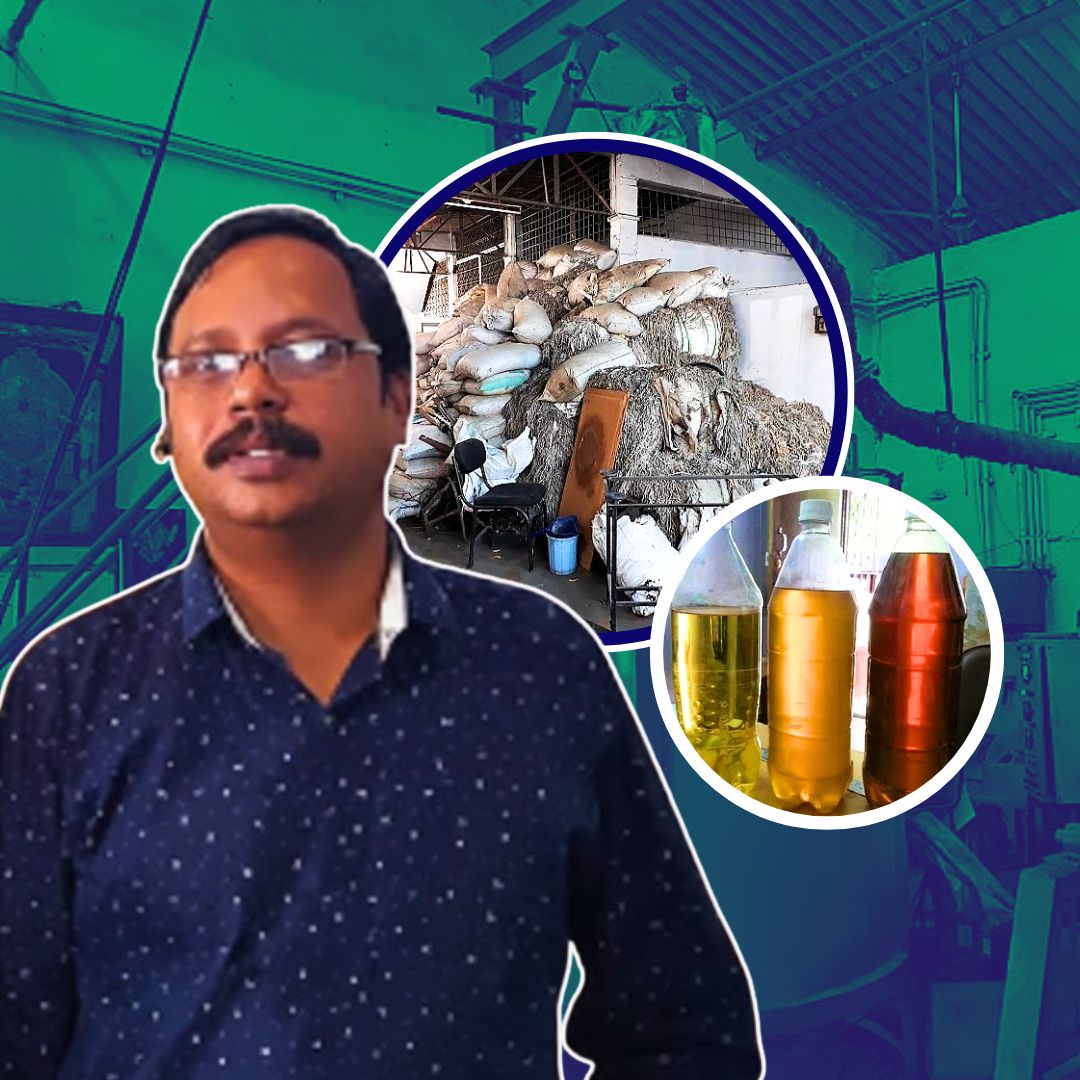

Hyderabad mechanical engineer and professor Satish Kumar has converted more than 50 tonnes of non-recyclable plastic into usable fuel since 2016 using a three-step plastic-to-fuel process, selling it at approximately ₹40–₹50 per litre to local industries.

In a country grappling with mounting plastic pollution and rising fuel costs, an unconventional solution has emerged from a small unit in Hyderabad. Mechanical engineer Satish Kumar, 45, has devised a technology that converts otherwise non-recyclable plastic waste into combustible fuels, including petrol, diesel and even aviation fuel.

The process used is called plastic pyrolysis – a method where waste plastics are heated in the absence of oxygen, causing them to break down into liquid fuels through depolymerisation, gasification and condensation. About 500 kilograms of end-of-life plastic can yield roughly 400 litres of fuel, he explains.

The process is conducted under vacuum conditions and, according to Kumar, it requires no water, produces no wastewater and generates minimal air emissions because the reactions occur in a controlled environment.

Registered under the Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) as Hydroxy Systems Pvt Ltd, Kumar’s unit currently processes around 200 kilograms of plastic per day, producing about 200 litres of fuel daily, which he sells to local industries at affordable rates of ₹40–₹50 per litre – significantly lower than market petrol prices.

While mainstream usage in motor vehicles has yet to be verified by regulatory agencies, some small enterprises are already using this synthetic fuel for industrial applications, such as powering broilers in bakeries and generators.

Voices from the Field: Innovator and Experts Weigh In

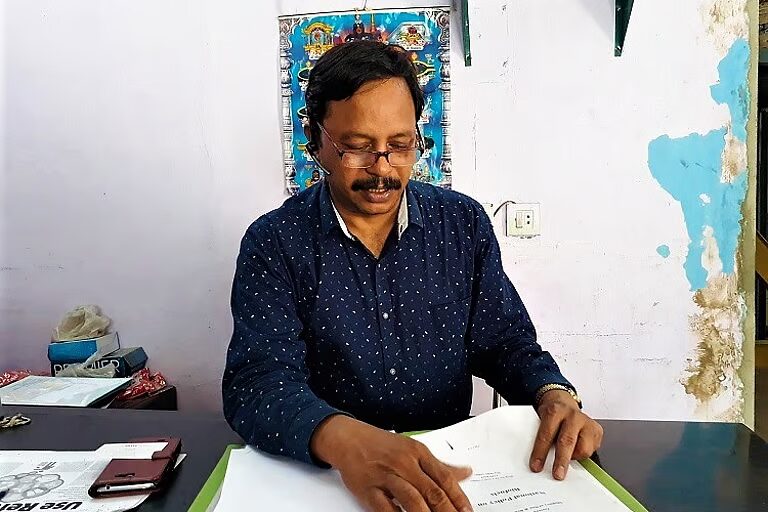

Speaking on his motivation, Kumar has repeatedly emphasised that his work is driven by environmental purpose rather than commercial profit. “Our main aim behind starting this plant was to help the environment. We are not expecting commercial benefits.

We are only trying to do our bit to ensure a cleaner future and are ready to share our technology with any interested entrepreneur,” he told media outlets reporting on his innovation.

Supporters of such grassroots innovations point to the dual benefit of tackling both plastic waste and energy scarcity. Proponents argue that converting plastics – which are derived from fossil hydrocarbons – back into fuel is a creative reuse of material that would otherwise linger for decades in landfills or oceans.

Researchers in similar areas of waste management echo the need for diversified technological approaches as part of broader sustainability strategies.

However, some experts caution that technologies like pyrolysis, while promising, must be evaluated critically. Environmental engineers emphasise that pyrolysis requires energy input – and the overall lifecycle impact, including energy efficiency and emissions from burning the resulting fuel, must be carefully assessed before large-scale deployment.

Background

India generates millions of tonnes of plastic waste annually, driven by rapid urbanisation and a growing economy. A significant portion of this – especially multi-layered and end-of-life plastics – cannot be mechanically recycled and ends up in landfills, waterways or open dumps.

Despite a national ban on many single-use plastics and strengthened rules on Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), enforcement remains inconsistent. Many civic bodies and waste management authorities struggle with collection, segregation and processing infrastructure, particularly for complex plastics.

In this context, small-scale technologies such as plastic pyrolysis are gaining attention as potential complementary tools for handling residual waste that conventional recycling systems cannot process.

Yet, policymakers and environmental regulators stress that these should not replace upstream efforts to reduce plastic use and promote reuse and reduction strategies.

The Promise and the Path Ahead

Kumar’s project highlights both the potential and the limitations of community-led technological innovation. On the one hand, his work demonstrates that creative engineering can convert environmental liabilities into useful products at a grassroots level.

His affordable fuel could offer cost savings for local industries struggling with high energy prices, while also demonstrating a model for value addition from waste.

On the other hand, the technology still faces hurdles in terms of scaling, regulatory certification and integration with broader waste management systems. Questions remain about the energy balance and environmental footprint of converting plastic into fuel, compared with other forms of renewable energy or material-to-material recycling.

Experts also emphasise that innovations like Kumar’s should go hand in hand with responsible consumption and waste reduction, not as an excuse to sustain high levels of plastic production. Policies that encourage circular economy models – including design for recyclability, deposit-return schemes and stronger EPR enforcement -are essential to complement such technological experiments.

The Logical Indian’s Perspective

At a time when environmental narratives can be dominated by despair, Satish Kumar’s work offers a refreshing example of purposeful innovation that tackles two critical challenges: plastic pollution and energy demand.

His journey reminds us that solutions do not always originate from large institutions; often, they emerge from individuals willing to experiment, learn and contribute to the collective good. Yet, while celebrating such ingenuity, we also stress the importance of rigorous evaluation, regulatory oversight and alignment with long-term sustainability goals.

Real progress demands systemic change – reducing plastic consumption, improving waste segregation, advancing recycling technologies, and fostering supportive public policy.

Community innovators can light the way, but collaboration among citizens, scientists, industry and government is essential to scale impact meaningfully.