Barely a month ago, the mysterious death of US citizen John Allen Chau in the most untouched island of India fuelled a lot of questions. The incident brought into the limelight the primitive and endangered Sentinelese tribe, who, reportedly, belong to the list of the last ‘uncontacted’ people in the world.

The North Sentinel Islands of Andaman & Nicobar has been declared a restricted zone by the Government of India up to a radius of three miles, in order to preserve the last surviving members of the primal community. As per the 2011 census data, their population has shrunk to around 40. The urban myths about the Sentinelese people have portrayed them as a brutal, aggressive race who do not waste a second in killing any modern human who tries to set foot on their pristine premises.

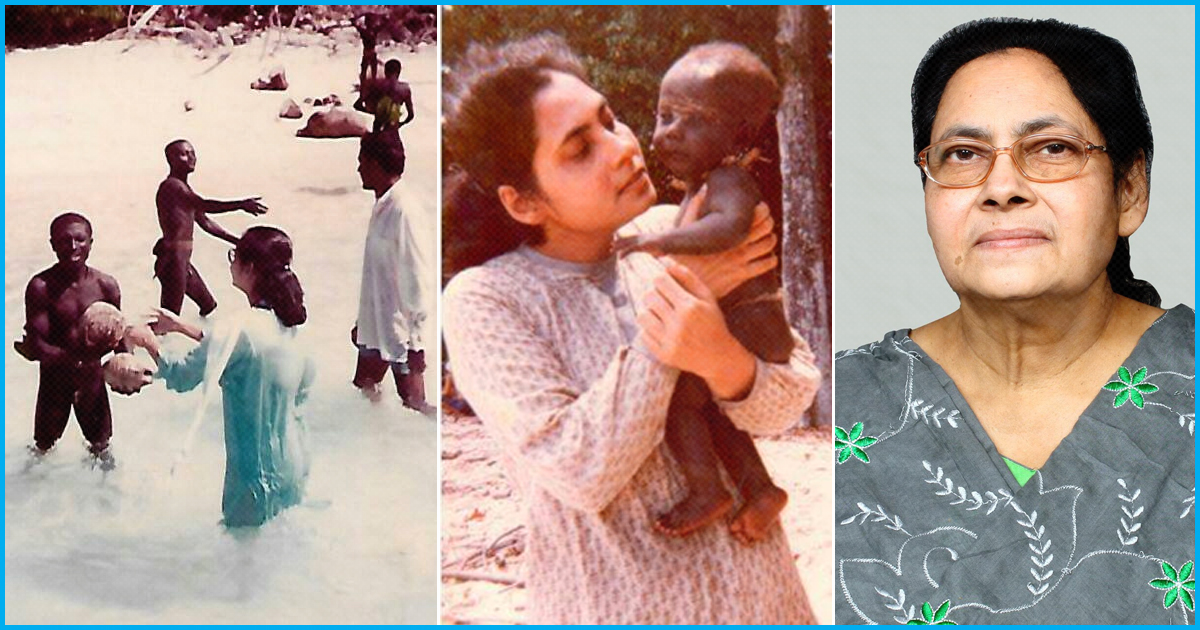

However, little known is that less than three decades ago, a woman anthropologist had not only succeeded in reaching the North Sentinel Islands but also fostered a beautiful friendship with these tribals. The Logical Indian got in touch with Dr Madhumala Chattopadhyay, author of the book ‘Tribes of Car Nicobar’, who narrated her interactive experience that surely surpasses a nail-biting thriller. Here are some excerpts from the interview.

We have heard that you had an interest in the Andaman aborigines from your childhood. How did that happen?

I was born and brought up in Kolkata. When I was studying in 7th Standard, I came across an article in a local Bengali daily about the Onge tribe of the Andamans. It intrigued me. I ran to my father and pleaded him to take me to these islands on a vacation. My father patiently explained to me that only researchers can access this place, that too with special permission. I was disheartened a little, but the idea always lurked in my mind.

Did this urge prompt you to study Anthropology?

My taking up Anthropology was another interesting story. During my college admission, I also thought of opting for basic science streams like Chemistry, Botany or Zoology. Then I heard about this subject, Anthropology, from one of the college authorities. I rushed to the library and looked the word upon a dictionary. Learning the meaning triggered my childhood wish to visit and interact with the Andaman aboriginal tribes one day. I did not hesitate to choose Anthropology then.

How did your interaction with these tribal communities happen?

My PhD research on “Bio-Anthropological profile of mother and child health in Car Nicobar Islands”, gave me a lot of insights into the unique lifestyle of these communities. I was selected for the post of Research Associate by Anthropological Survey of India (ASI), and I opted for their Port Blair centre. From 1989 to 1996, I stayed in Port Blair. Whenever I got time from the mandated national research programmes, I participated in occasional expeditions to these ‘untouched’ islands as part of my personal research.

Being the first woman in history to venture among these ancient tribes, did you face any objections from your family or academic circle?

Even in the patriarchal society we live in, I was lucky to have the complete support of my mother. She said that she had full confidence in her brave daughter and would not hesitate to send her anywhere in the world. In fact, every time I went on an expedition to the Sentinel Islands or the Jarawa settlements, my family had to give a signed undertaking that in the event of my death by unavoidable circumstances, ASI cannot be held responsible. I got the undertaking from my family every time, without any hitch.

I remember when the Sentinelese expedition was on cards, one person joked with our Regional Officer, “Let Madhumala go, there is no one to cry for her if she dies there.” Of course, I didn’t die, rather our expedition scripted history.

The Sentinelese tribes are feared as the most aggressive primal tribes. How did you succeed to develop a friendly contact with them? Share your experience.

The Sentinelese have turned hostile towards modern humans after a traumatic interaction with the British in the last century. After that, all attempts of contact (even distance contact) have been thwarted by their arrow attacks. Only six months ago, their poison arrow had injured the Lieutenant Governor. So the thirteen members of our team were all going with a huge life risk.

In the early morning of January 4, 1991, our journey commenced on a small ship MV Tarmugli. We reached within 50 metres of the island shore, which is well-within their arrow range, at “Allen Point”.

After waiting for a long time to spot at least one of them, we saw smoke coming up from one direction of the island. We diverted the ship and sailed towards that direction.

We were carrying gunny bags full of coconuts as gifts for them. As soon as we spotted a few of the Sentinelese people, we started floating coconuts towards them. They were apprehensive at first but soon they started distributing those among themselves. Soon, I was handing over coconuts directly to them. They were in quite a playful mood.

Suddenly, one of our team members shouted, “Teer Uthaya! Teer Uthaya! (They are targetting with arrows)”. Startled, we found that only one 19 or 20-year-old boy was aiming his bow and arrow at us. Instantly, I spotted one woman beside him, who seemed to be the boy’s mother. I addressed her as “Kairi Sera (Mother, come near)” in Onge and conveyed to her “Nariyali Jaba Jaba (More and more coconuts).” She realised my gesture and immediately distracted the boy aiming the arrow. Quick wit had saved me that day.

A month later, we again visited the Sentinel Islands and this time also, our interaction went smoothly.

You were also the first woman to interact with the Jarawas. How was your experience with them?

The day after the first Sentinelese expedition, we set sail for the Jarawa habitat on January 5, 1991. We had in our team Police Superintendent Bakhtawar Singh, who was the first person in history to establish friendly contact with the Jarawas in 1966. I was the first ever woman to be doing the same. We reached the seashore, but my male colleagues forbade me to step out of the boat fearing my safety. Seeing my eagerness and insistence, they allowed me to join them, but at my own risk. In a few minutes, a few curious Jarawa men climbed onto our boat and were slowly coming towards me with curiosity. The boatman shouted to me, “Didi, Jump Karo pani me (Quickly dive into the water)”. But, I am not a very good swimmer so I kept seated calmly. When the Jarawa men were standing close to me. I had the sense that they would not harm me, they were just curious about the appearance of a stranger.

Then a Jarawa lady went ahead and sat beside me. I smilingly told her in Onge language that I am also a woman, just like her. Soon, a little girl of 11 or 12 years climbed onto my lap fearlessly.

It did not take much time for me to blend in with them. They gifted me their traditional ornaments and headgears made of tree barks and other natural items.

On our next day trip, the tribal women danced and sang around me, as if I am one of their own. You know, they had taken my measurements the day before and made customised ornaments for me. It was an exhilarating experience.

What is your opinion with regards to US citizen John Allen Chau who was recently killed by the Sentinelese?

They are a very small, isolated group. We, modern humans, should not try to impose our modern habits and practices on them. The American tourist John Allen Chau tried to impose his Catholic faith on these nature worshippers and became a victim.

First and foremost, nobody should be allowed to step on the island without official permission and guidance from the Andaman administration.

Also, let me tell you something. The infamous hostility of these tribes is a misconception to some extent. They will not attack someone instantly. If they are displeased with an outsider, first they will show their weapons to show resistance and incite fear. The wisest thing to do is to retreat then and there. But, if someone does not, the tribe would not hesitate to kill them. They are extremely against any outsider trying to penetrate the island interiors into their habitat.

They are so well-blended with nature that they even survived the devastating Tsunami. So it is best if we leave them as they are, but do provide modern medicinal support in case of a calamity or endemic.

Also Read: American Missionary Death: Activists Say Retrieving The Body Can Lead To Extinction Of Tribe