“Coming out as a Muslim queer is a big challenge. You are a minority within a minority.”

Rashid*, who self-identifies with the pronoun “they/them”, is a minority within a minority. Rashid’s problem? They don’t fit into the binary system of male and female that is determined by the society – from separate toilets to separate clothing to separate schools. That is why they call themselves “queer”: Queer people are either not heterosexual or their gender does not match the sex they were assigned to at birth, and they don’t identify with the heterosexual norms of society. “I don’t feel male,” is what Rashid said to one of their (Rashid’s) siblings, after years of bullying at school, where others called them (Rashid) gay, where they had suffered from depression, anxiety and an eating disorder.

Rashid is 23. They grew up in the Middle East in a “pretty well educated” Indian family, as they say, with his parents working in the health sector. For College, Rashid moved to Bangalore, where one of their siblings already lived. By saying “I don’t feel male,” Rashid didn’t mean to say they were gay – “I didn’t say I’m feminine either. I felt like something in the middle.” But the middle, the grey area, is harder for others to understand.

Rashid’s parents and daughter’s fear was triggered by the thought that their son and brother might be gay. Such views of homosexuality being a threat may be widely found even amongst healthcare professionals. In 2014, the immediate past president of Indian Psychiatric Society (IPS), Dr. Indira Sharma, said in an interview to The Times of India that “[t]he manner in which homosexuals have brought the talk of sex to the roads […] is unnatural. Our society doesn’t talk about sex”, thus reinforcing a conception of homosexuality as being ‘unnatural’ that was reflected in the Indian penal code until 2018. Even if the IPS later distanced itself from the comment and said it was not its official view, the statement is revealing of at least a part of a medical profession in India that sees homosexuality as something abnormal that needs to be cured.

After opening up to their family three years ago, and after Rashid was void of digital communication and restricted to contact others by their family, a long odyssey of treatments and visits to different doctors started and thus depression. “For Indian parents, depression is a ‘white’ thing that comes only to rich people. They would always find better reasons for your illness, like: ‘You use your phone too much, that’s why you get depressed.’ They see it as a Western concept. Also in school, no one talks about the possibility that one could have eating disorders or anxiety.”

Confronted with their depression, psychiatrists told Rashid that they were faking, or diverting discussion of bad grades. Their proctor at college recommended they eat cucumbers to cure their depression – a dubious approach to a disease that, according to the World Health Organization, is a major cause of suicide.

Among the many humiliating and ineffective therapies Rashid underwent, they remember electroshock therapy and a so-called ‘orgasm therapy’ in which the patient is shown potentially sexually stimulating images to then check the neural responses. “Of course the test came up with nothing,” Rashid says, “because I controlled myself.” The test in itself mirrors the (mis)conception that sexuality – and even more so homosexuality – is something uncontrollable, that by mere seeing an erotic image in a sterile atmosphere like a clinic you would reach orgasm.

Because of Rashid’s unclear state of mind about their sexuality, their parents thought Rashid might be suffering from a multiple personality disorder, and send them to a behavioural therapist, the first doctor Rashid felt understood by. “You are like a potato in biryani, you just need to navigate your life,” she told Rashid, and gave them the feeling that it was not they who were wrong, but those surrounding them who could not cope with their ‘difference’.

The therapy was very expensive; Rashid had to stop it after five months. At this point, Rashid’s parents sought the solution in religion. “They wanted to pray the gay away,” says Rashid with a twinkle in their eyes.

When a genetic test brought evidence that Rashid’s testosterone level was very low and the oestrogen producing hormones FSH and LH very high, their parents convinced Rashid to start hormone therapy. The injections caused rashes, headaches, stomach cramps and vomiting. It turned out later that the daily dose was far too high, and that Rashid was allergic to the injections. When Rashid confronted the endocrinologist with a long list of acknowledged potential side effects that all fitted Rashid’s symptoms, the doctor tore it up and threw it into the bin. Rashid needed to become ‘normal’ again, the expert told them. Not only did the therapy cause them pain, Rashid was also emotionally and sexually abused by the endocrinologist, and by nurses, who accused them of “whoring around, as Muslims do.”

During all these different therapies Rashid thought about committing suicide. “The hormone therapy caused in me the feeling of being something that was flawed, of being a sin. It made me believe I am wrong, and that this is a punishment by God.”

Finally, after a year of conversion therapy, things changed: Rashid met a drag queen for the first time in their life, at an event put on by Human Library, an NGO fighting worldwide against prejudices. She encouraged them to go to his first Pride March. The day after, Rashid’s mother said that they would stop conversion therapy for a couple of months because the side effects were too severe.

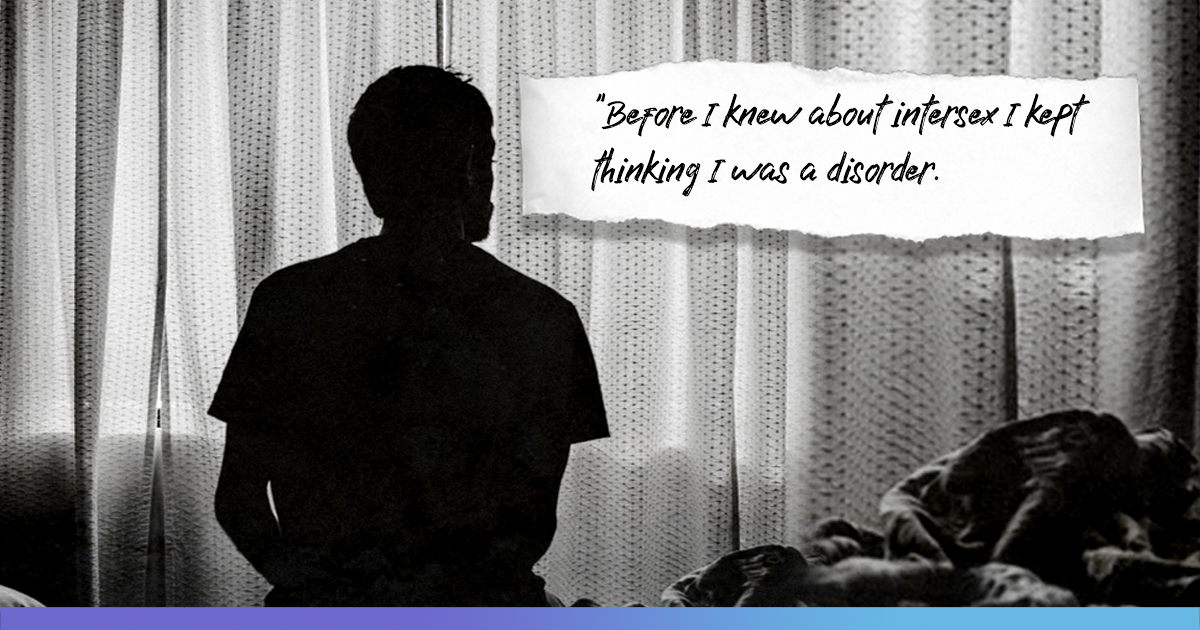

And Rashid encountered the concept of ‘intersex’. Being treated as a “genetic disorder,” Rashid says, “I kept thinking I was a disorder.” Rashid learnt that more than 1% of the world’s population has variations in sexual characteristics like chromosomes or genitals, which are just a natural play of nature. Some of Rashid’s chromosomes, for example, are XXY, some are XXXY. Finally, Rashid found a good endocrinologist who was primarily concerned about their well-being. She explained to Rashid’s parents, who have a medical background, that hormones don’t change the sexual orientation, and that being a queer is normal. As their first intersex patient, Rashid became a study object for their doctors. Even if Rashid didn’t feel good about it, they were open to their examinations – “so that others can learn.”

Rashid became an advocate of Human Library – presenting a ‘human book’ which is open for questions from the public about their person. Rashid was invited to speak about their story at Queer Campus Bangalore, a safe space for queer students and young professionals. “There were people like me here, but open and vibrant about themselves, who had no fear.” Rashid’s self-confidence about being a queer intersex Muslim has grown since then. “Coming out as a Muslim queer is a big challenge. You are a minority within a minority. Queer confidence and queer visibility come only with queer safety. That is why we need safe spaces like Queer Campus.” Along with their Masters in natural sciences, Rashid works as a safe space manager in collaboration with United Nations Women, specifically the UN Arabic branch. They have been involved in creating safe spaces for queer refugees in Lebanon, Turkey and Egypt.

Working with the UN and with queer refugees has taught Rashid about their privileges: “I can go to a coffee shop and understand what the person behind the counter is saying. I understand the struggles I’ve gone through, and I understand that I can seek help. I can speak up and express my opinion. I can do these things with ease, others not.”

Despite these privileges, Rashid leads a life of excuses, of juggling their personal freedom and the well-being of their family. “It’s like living two different lives. It’s not just your safety you have to look at, but also that of your brother-in-law, sister-in-law, your cousins. What you do and say will create hurdles for the whole family.”

Opening up, working in a queer community, in safe spaces, saved Rashid’s life. Now they want to widen access to these spaces, and enable others to live a life in which they can express themselves freely. “I want to create tiny ripples. Because ripples lead to big waves. And waves bring change.”

*For anonymity, name is changed.

Also Read: This 28-Yr-Old Who Runs Queer Muslim Project Is Part Of UN Task Force On Gender Equality