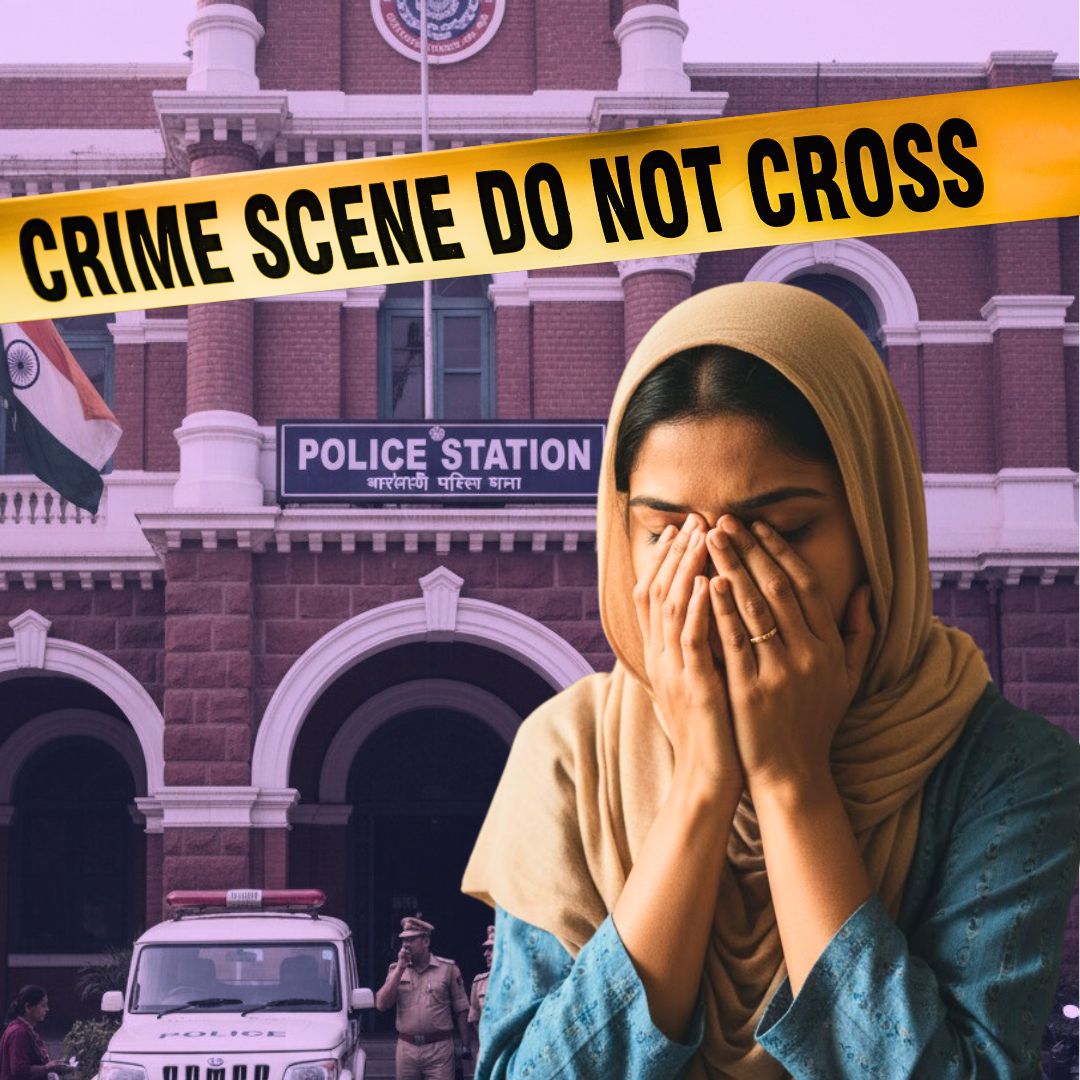

A woman in Uttar Pradesh’s Amroha district alleges she was violently exploited and gang‑raped under the pretext of nikah halala after being divorced by instant triple talaq, triggering a police investigation and renewed scrutiny of personal law, consent and legal protections.

A deeply disturbing case has emerged from Said Nagli in Uttar Pradesh’s Amroha district, where a woman has accused her husband, relatives and local clerics of subjecting her to repeated sexual violence under the guise of nikah halala, a religiously framed practice said to allow remarriage after triple talaq.

According to the First Information Report (FIR) filed on 9 December 2025, the complainant – identified in reports as Zubaida – alleges that she was forcefully married at 15, divorced through instant triple talaq twice, and then coerced into undergoing halala multiple times to reunite with her husband.

The FIR, registered at Said Nagli police station, accuses her husband Nawaz, his cousin, a hakim (traditional healer) and others of threats, intimidation, coercion and alleged gang rape under the false pretext that the halala process was necessary for her to return to marital life.

Police have invoked Sections 3 and 4 of the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Act, 2019, which criminalises instant triple talaq, along with multiple provisions of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita relating to rape, grievous hurt, criminal conspiracy and intimidation.

Station House Officer Vikas Sahrawat confirmed the arrest of the husband, while teams continue to search for others named in the FIR. “Further action will depend on corroboration and evidence,” he told reporters.

The FIR’s scope was widened when police added sections of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, after examining the woman’s age at the time of her marriage.

What Halala Is – And Why It’s Contested

Under certain interpretations of Muslim personal law, nikah halala is understood as a process in which a woman who has been divorced by triple talaq must marry, consummate that marriage, and then divorce her new husband before remarrying her former spouse.

Crucially, halala itself has no statutory basis in Indian law, and is not mentioned in the Muslim Women Act of 2019.

Legal experts and women’s rights activists argue that this absence of codification leaves a large grey area where customary or patriarchal interpretations can be imposed without oversight or clear procedural safeguards.

As one advocate put it, halala is often misinterpreted and manipulated, particularly in informal village settings or under pressure from family and clerical figures.

The complainant’s narrative stretches across nearly a decade: married off in 2015 at 15, divorced via instant triple talaq in 2016 and again in 2021, and subjected to what she describes as a pattern of abuse disguised as religious reconciliation attempts.

After years of being a single mother and facing financial hardship, she said she accepted the promise of remarriage – only to find herself once again trapped in coercive arrangements. “It was after a long time that I realised what had happened to me was wrong,” she told police, according to reports.

Legal Gaps, Personal Law and Rights Discourse

This case has sharply drawn attention to ongoing legal ambiguities concerning personal law, women’s rights and marriageable age. While instant triple talaq was criminalised in 2019, India does not have a uniform civil code, and Muslim personal law remains largely uncodified and inconsistently interpreted in courts.

Importantly, Muslim personal law does not prescribe a minimum age of marriage – instead linking marriageability to puberty, an interpretation contested by activists and legal scholars.

This has wider implications for how cases involving child marriage, coercion and consent are legally approached and prosecuted.

Activists note that practices like halala often operate in informal spaces with little documentation or legal oversight, leaving victims without recourse until they approach law enforcement.

“In many cases, women don’t even know that what is being done to them is wrong,” said Zakia Soman, founder of the Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan, highlighting a culture of silence and structural obstacles that keep harmful practices hidden.

The absence of mandatory registration for marriages and divorces exacerbates these issues, placing the burden of proof heavily on survivors and complicating prosecutions in cases with limited written evidence.

Official Statements and Contesting Narratives

Police have stressed that the investigation remains active, with only the husband in custody so far and other accused believed to be absconding. “We are following leads and gathering evidence,” an Amroha police official remarked in a statement to The Times of India.

The arrested husband, meanwhile, has filed his own complaint alleging harassment and threats by the woman and her relatives – a reminder that criminal cases can be fraught and contested at multiple levels.

No official statements from community or religious organisations have been widely reported at the time of writing. However, the case has prompted renewed debate among legal experts, activists and policy analysts about the implementation of personal law protections and the limits of customary practices.

Broader Implications and Continuing Controversies

While this particular case is exceptionally severe due to the alleged pattern of abuse and violence, similar incidents – where women have been exploited under the pretext of religiously framed halala arrangements – have been reported in other parts of Uttar Pradesh and beyond in past years.

These underscore broader societal and legal challenges, including patriarchy, economic dependence, stigma and limited access to justice.

Critics of the legal system argue that criminalising one aspect of personal law (instant triple talaq) without addressing surrounding practices like halala, documentation of marriages, and consent frameworks creates an incomplete protective apparatus for women.

The Logical Indian’s Perspective

At The Logical Indian, we affirm that no tradition or belief, however long‑standing, can be permitted to justify violence, coercion or the denial of a woman’s agency.

Personal laws must be interpreted in ways that uphold constitutional values, human rights and gender equality. This case stands as a powerful reminder of the gaps that remain between legal protections and lived realities – particularly for marginalised women.

We call for inclusive dialogue, stronger legal clarity, mandatory documentation of personal law practices and community education that centres consent, dignity and justice for all.