In 1996, Balmati Naik died of starvation in Barlabaheli village, Odisha, leaving behind her six-year-old orphan, Gundhar. Two decades on, this reporter revisits the village looking for the young man and traces his continuing story of struggle

Is Gundhar Naik home, I asked a woman scrubbing pots and pans outside the house next door.

“Where have you come from, and what do you want here?” she demanded.

I am a journalist from Khariar who has written stories about Gundhar in the past, I explained. I have come to find out how he is doing.

The woman looked closely at me and asked, “Are you Thakurji?” Yes, I said, pleased that she had recognized me after all this time.

I had visited Barlabaheli village in Bangomunda block of Bolangir district, Odisha, several times in 1996-97. Now I was back after a gap of nearly two decades.

In 1996, a severe drought in western Odisha – across Bolangir, Nuapada and other districts – had caused hunger and starvation. It led to an exodus – many migrated for work to the brick kilns of Andhra Pradesh. Sadly, it was not unusual for this area – every 2-3 years a drought caused such conditions at that time.

Balmati Naik, alias Ghamela, a 32-year-old Adivasi widow of an agricultural laborer, was one of around 300 residents of Barlabaheli village. Her husband had died two years earlier. Ghamela had been forced to give up the little piece of land they owned to repay a loan. She worked as a daily-wage laborer but following the drought, there was no work to be found in the village. Her six-year-old son Gundhar and she were starving. The locals claimed they had informed block development officials of Ghamela’s situation before her death, but they did nothing.

On September 6, 1996, after roughly 15 days of starvation, Ghamela died. Many hours later, the neighbors had found her son screaming and crying beside her body.

My stories on this starvation-driven death and its aftermath were published in Dainik Bhaskar in October 1996. Local social workers and some opposition leaders visited the village and took up the issue. Members of the Human Rights Commission also came and noted that it was a death caused by starvation. Political leaders, the block development officers, the district collector and district magistrate made tracks to the village. Even the then Prime Minister H.D. Deve Gowda was scheduled to visit, as part of his tour of drought-hit regions, but did not show up.

The villagers told the visiting officials that employment opportunities were what they needed most. But when they pressed their case, village leaders had alleged, the district magistrate warned them not to play politics or take their protests too far, or the village would be denied the few benefits (such as ration cards) it was getting.

After his mother’s death, Gundhar was very weak. Local panchayat leaders took the child to Khariar Mission Hospital, nine kilometres away, where he was diagnosed with severe malnutrition and cerebral malaria. He was critically ill, but survived.

After he recovered, Gundhar was sent back to the village. The national media arrived to cover the story. The district administration granted him Rs. 5,000 – a fixed deposit of Rs. 3,000 and Rs. 2,000 in a savings account. And with that they washed their hands of the orphan.

For 19 years, I had wondered what had happened to Gundhar.

Ghamela’s husband had a son, Sushil, from a previous marriage. When she died, he was around 20 years old and working at a road construction site on the Khariar-Bhawanipatna road.

The neighbour told me that Gundhar now works at the Pappu Rice Mill in Tukla village, less than five kilometers from Barlabaheli . His in-laws live in Tukla, she added, and he has a two-month-old baby. His stepbrother works as a haliya (helper) at a nearby farm.

Riding my motorcycle over the ridges of the fields, I found the farm where Sushil was tilling the land owned by his employer. His three daughters and a son were nearby. Sushil, now 40, was unmarried when I had met him following Gundhar’s mother’s death. He did not recognise me, but when I reminded him of the stories I had written, he remembered.

Sushil is paid Rs. 4,000 a month, or Rs. 130 per day, on which the family subsists. Some of his kids had clothes on, some did not. Their poverty was evident.

I left for Tukla to meet Gundhar. At the Pappu Rice Mill I met the owner Pappu, and he informed me that Gundhar had gone to his village that day. I went to his in-laws’ house where I met his wife Rashmita, who was holding their baby boy, Subham. Her husband had gone to Barlabaheli to clean the house and had been gone a long time, she said.

Top: Gundhar’s wife Rashmita (standing, left), his sister-in-law, and parents-in-lawoutside their house in Tukla village.

Bottom: Rashmita and their son Subham

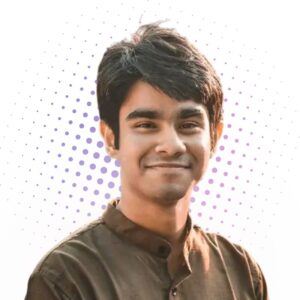

I went back to Barlabaheli. Gundhar was indeed at the house. He smiled and greeted me. The six-year-old had become a young man, a husband and a father. But there was…