In a landmark judgment, the Supreme Court has recognised menstrual health as a fundamental right, ordering free sanitary pads and adequate hygiene facilities in schools nationwide, linking dignity, education, and equality for adolescent girls.

In a significant step towards gender justice and public health equity, the Supreme Court of India has ruled that access to menstrual hygiene is a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to life with dignity.

The court held that menstrual health is inseparable from physical well-being, mental health, privacy, and education, particularly for adolescent girls from marginalised backgrounds.

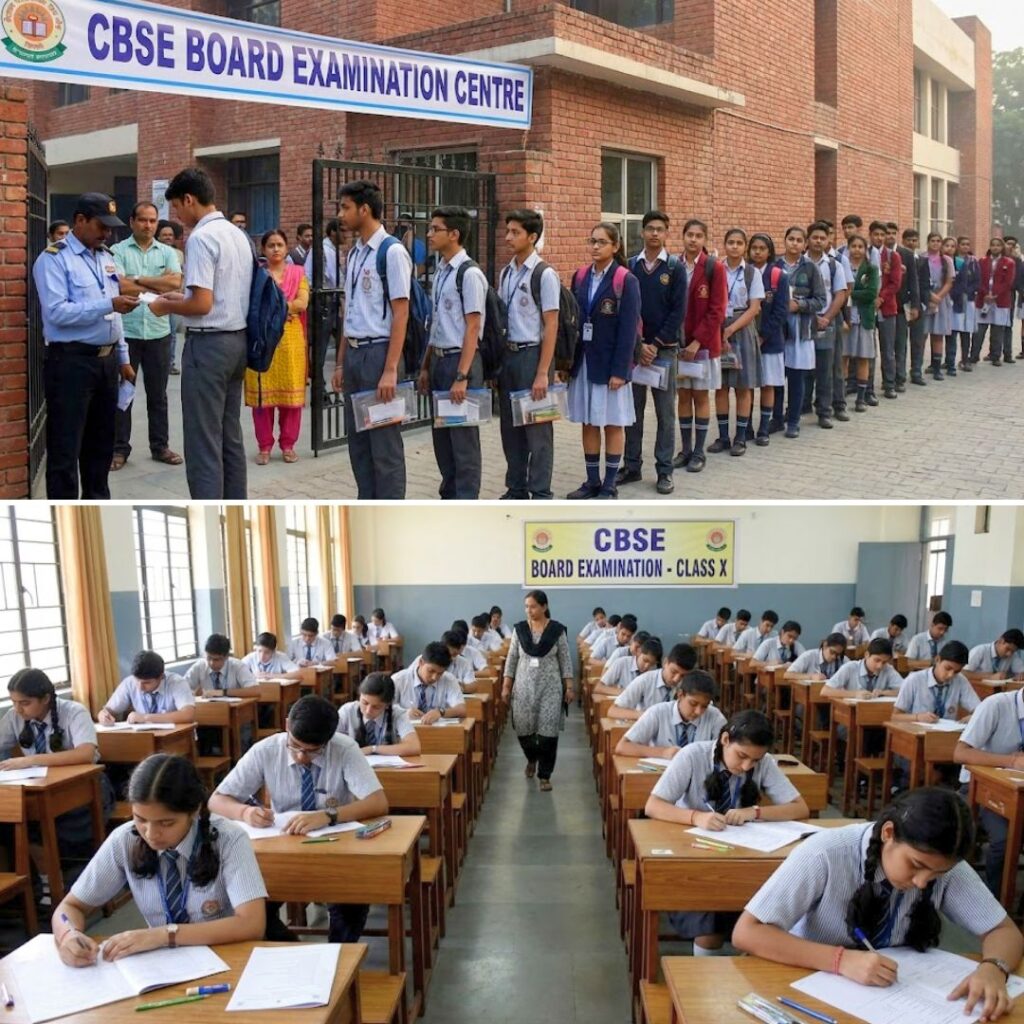

The ruling came while hearing a public interest litigation seeking uniform implementation of menstrual hygiene measures in schools across the country. A bench comprising Justices J B Pardiwala and R Mahadevan observed that menstruation is a natural biological process and that systemic neglect around it has long resulted in stigma, shame, and exclusion, especially within educational spaces.

The court made it clear that constitutional rights cannot be compromised due to administrative gaps or social discomfort.

Free Sanitary Pads and School-Level Facilities Mandated

The apex court directed both government and private schools to ensure the free availability of sanitary pads for girls studying from Classes 6 to 12. Stressing environmental responsibility, it recommended the use of biodegradable menstrual products wherever possible.

The court also ordered that these products be made available in a manner that preserves privacy, including through vending machines or designated menstrual hygiene corners within school premises.

Beyond product access, the judgment laid emphasis on infrastructure. Schools have been instructed to provide separate, functional, and disabled-friendly toilets for girls, with assured water supply, soap, and proper waste disposal mechanisms. The bench warned that failure to comply could invite strict action, including derecognition of non-compliant institutions, underscoring that menstrual dignity is not optional but a legal obligation.

Education, Attendance, and the Hidden Cost of Stigma

During the proceedings, the court noted that lack of menstrual hygiene facilities remains a major contributor to absenteeism and drop-outs among adolescent girls, particularly in rural and low-income urban areas.

Studies cited in earlier hearings have shown that many girls miss several school days each month due to inadequate access to sanitary products, safe toilets, or fear of embarrassment.

The judges observed that such barriers have long-term consequences, limiting educational attainment and reinforcing gender inequality. By linking menstrual health directly to the right to education, the court reframed the issue not as a welfare measure, but as a matter of equal opportunity.

It stressed that denying girls the means to manage menstruation safely and with dignity effectively excludes them from public life.

Government’s Stand and Existing Policy Framework

Representatives of the Union government informed the court that a Menstrual Hygiene Policy for school-going girls had been approved, aimed at improving awareness, access to products, and sanitation infrastructure.

Several states also cited existing schemes under which sanitary pads are distributed through schools, anganwadi centres, or health departments.

However, the court noted that implementation across states remains uneven, with stark disparities between urban and rural regions. While some states have robust distribution systems and awareness programmes, others continue to struggle with funding, supply chains, and social resistance.

The bench emphasised that constitutional rights cannot depend on a person’s postcode and called for a uniform, enforceable framework applicable nationwide.

From Policy Promises to Ground Reality

The judgment follows years of advocacy by public health experts, educators, and civil society organisations, who have highlighted how menstrual stigma intersects with poverty, caste, disability, and geography.

Petitioners pointed out that even where schemes exist, lack of monitoring often leads to irregular supply, poor-quality products, or complete non-availability in schools.

The court acknowledged these concerns, directing states and Union Territories to ensure accountability mechanisms and regular audits of school facilities.

It also recommended menstrual hygiene education as part of school curricula, stressing that awareness among boys, teachers, and parents is essential to dismantle stigma and create supportive environments for menstruating students.

Menstrual Dignity as a Human Rights Issue

In strong observations, the bench stated that treating menstruation as a taboo has historically pushed it into the shadows, leading to silence, misinformation, and neglect. It reiterated that menstrual health is not a matter of charity or moral policing, but a core human rights issue rooted in dignity, privacy, and equality.

By constitutionalising menstrual health, the court expanded the interpretation of Article 21, aligning it with international human rights standards that recognise sexual and reproductive health as integral to the right to life.

Legal experts have described the ruling as transformative, with potential implications for policy-making, budget allocations, and gender-sensitive governance.

The Logical Indian’s Perspective

The Supreme Court’s ruling is a powerful reminder that dignity cannot be selective. Recognising menstrual health as a fundamental right affirms that young girls deserve safe, inclusive, and supportive spaces to learn without shame or fear.

The Logical Indian believes that true progress will lie not only in distributing sanitary pads, but in changing mindsets-normalising conversations around menstruation, investing in infrastructure, and ensuring accountability at every level.