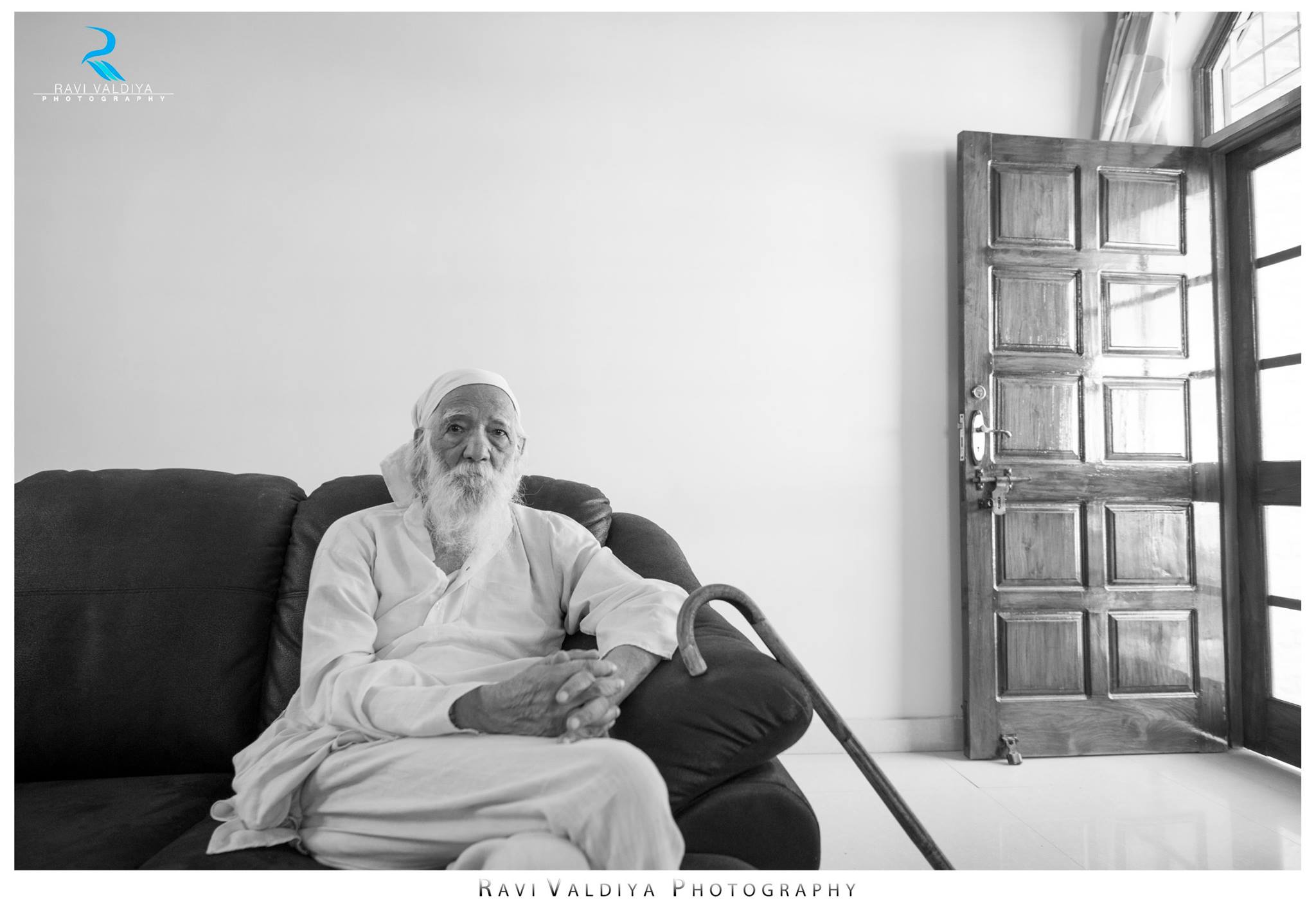

A Legend Who Gave 76 Years Of His Life To Social Work, Including Fight In Chipko, Against Untouchability And Anti-Liquor Drive

24 Oct 2016 6:30 AM GMT

Image Courtesy: Ravi Valdiya Photography

We all want the economic growth of our country. After all, that is what is going to take our country forward, make it a superpower and raise the living standards of the population. Surely, large infrastructure projects like dams, SEZs or providing land at concessional rates to the private investors does help in achieving this aim.

More often than not, these projects require large scale displacement of people. Almost always it is the tribals, the poor and the marginalised sections of the society who are expected to sacrifice in the name of national development. It is because these people reside in the mineral-rich zones or the hilly regions which are directly going to be affected by these projects; and these regions are also the one where the effect of socially-uplifting government policies has been the least.

There have been several large-scale protests against such projects and activities. One of the most prominent and watershed ones in independent India was the Chipko Movement, starting in the 1970s.

The name of the movement, when translated in Hindi means ‘to stick’ or ‘to embrace’. It started off in the in Chamoli district of now Uttarakhand region when the forest authorities granted licenses for commercial felling of the trees, but rejected a similar annual demand from the local population for cutting a few trees. The locals depended extensively on the trees for food and fuel and because of the role trees play in stabilising soil and water resources. When their requests and protests failed, and when the contractors came for cutting the trees, the local women embraced the trees to protect them from the axes. The protest soon spread to other parts of the region and later to other parts of the country.

Sunderlal Bahuguna, a Gandhian who had earlier fought against untouchability and also organised hill women in his anti-liquor drive, was a very important and prominent face of the Chipko movement. When he married his wife Vimla, they decided to live in a village and establish an ashram in the hills.

In the early 1980s Bahuguna made the movement even more popular by undertaking a 5,000-kilometre march through the Himalayas. He visited hundreds of villages in the region to spread awareness and gather support for the cause. He also met the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, a meeting that is credited for the ban on felling of trees for 15 years in the region. One other notable contribution of his to this cause, and to environmentalism in general, was his creation of the Chipko’s slogan ‘Ecology is permanent economy’.

Later, Bahuguna led the campaign against the construction of the Tehri Dam on the Bhagirathi. The dam caused the displacement of a large number of people, with some estimates putting the number around 1,00,000. Other concerns were its impact on the sensitive ecology of the region as well as its capacity to withstand an earthquake in a seismically active zone.

In fact, in December last year, the Union Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change submitted an affidavit in the Supreme Court accepting that the hydroelectric power projects did aggravate the impact of the flash floods in Uttarakhand in 2013. The Chopra committee, set up on the directions of the Supreme Court, also reached a similar finding in their report.

Bahuguna also undertook fasts to protest against the Tehri dam. In 1995, he called off a 45-day-long fast following an assurance from the then Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao. But when the promise was not kept, he went on another long fast which lasted for 74 days at Raj Ghat after which the government agreed to set up a review of the seismic, environmental and rehabilitation aspects of the project.

When the dam was completed and began to fill in 2004, Bahuguna and his wife, Vimla, were forcibly moved to a government allotted house upstream. He has vowed that this is not the end and he will continue to fight for ecological protection. He lives there today, and continues his environment work.

In an interview to Frontline magazine in August 2004, while referring to the Tehri Dam, he said: “The people have got a raw deal. Especially the villagers. Even if they have got land elsewhere, they have been deprived of their open spaces, which the mountains provided them. These open spaces used to meet their fodder, firewood and other requirements. Those spaces are no longer available to them. Besides, the sense of security, which used to be here, is not present in the areas to which they have been shifted. Men can no longer go out to work because they have to guard their houses. The spirit of freedom that a highlander enjoys has been taken away from us. There can be no financial compensation for that.”

In 1987, Chipko Movement was awarded the Right Livelihood Award and in 2009, Sunderlal Bahuguna was awarded with India’s second highest civilian honour, Padma Vibhushan.

All section

All section