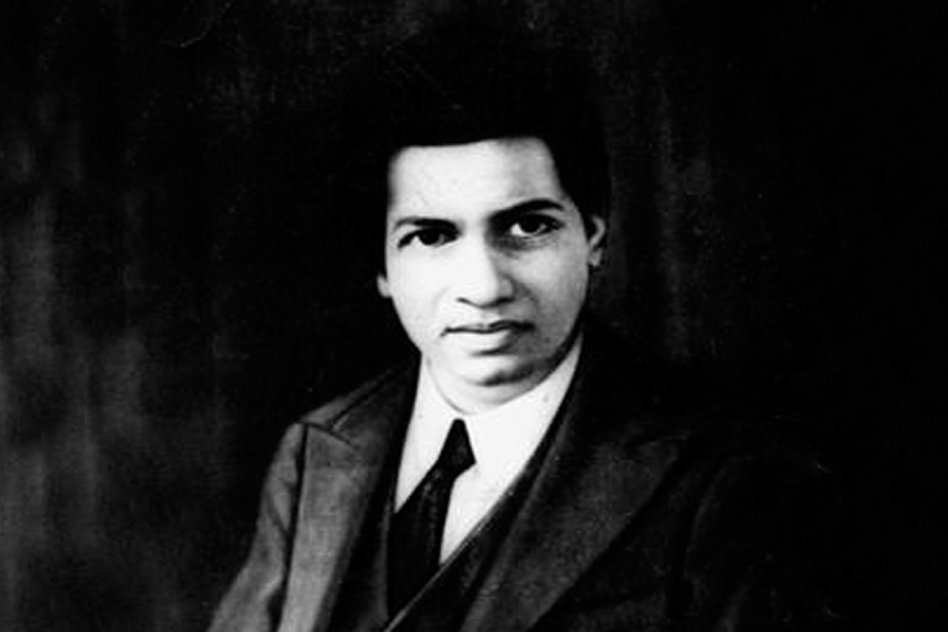

Image Courtesy: thehindu

“The Man Who Knew Infinity”, A Biopic On Indian Mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan

25 April 2016 6:22 PM GMT

India has been blessed with a genius Srinivasa Ramanujan. He was an Indian mathematician and autodidact who, with almost no formal training in pure mathematics, made extraordinary contributions to mathematical analysis, number theory, infinite series, and continued fractions. Living in India with no access to the larger mathematical community, which was centered in Europe at the time, Ramanujan developed his own mathematical research in isolation. As a result, he rediscovered known theorems in addition to producing new work. Ramanujan was said to be a natural genius by the English mathematician G. H. Hardy, in the same league as mathematicians such as Euler and Gauss. Ramanujan was born at Erode, Madras Presidency in a Tamil Brahmin family of Thenkalai Iyengar sect.

His introduction to formal mathematics began at age 10. He demonstrated a natural ability, and was given books on advanced trigonometry written by S. L. Loney that he mastered by the age of 12; he even discovered theorems of his own, and re-discovered Euler’s identity independently. He demonstrated unusual mathematical skills at school, winning accolades and awards. By 17, Ramanujan had conducted his own mathematical research on Bernoulli numbers and the Euler–Mascheroni constant.

Ramanujan received a scholarship to study at Government College in Kumbakonam, which was later rescinded when he failed his non- mathematical coursework. He joined another college to pursue independent mathematical research, working as a clerk in the Accountant- General’s office at the Madras Port Trust Office to support himself. In 1912–1913, he sent samples of his theorems to three academics at the University of Cambridge. G. H. Hardy, recognizing the brilliance of his work, invited Ramanujan to visit and work with him at Cambridge. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society and a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. Ramanujan died of illness, malnutrition, and possibly liver infection in 1920 at the age of 32.

During his short life, Ramanujan independently compiled nearly 3900 results (mostly identities and equations). Nearly all his claims have now been proven correct, although a small number of these results were actually false and some were already known. Amazingly, Ramanujan’s notes (almost 100 pages) from his last year of life made their way to England. They were almost incinerated in the 1960s, but were saved by Robert Rankin. Rankin saw to it that the notes were added to the Ramanujan archives at the Wren Library at Trinity College, Cambridge, where they laid forgotten until George Andrews discovered them in 1976. This “lost notebook,” as it is referred, includes some of Ramanujan’s most important works and constitutes the work that physicists and mathematicians are studying today in their work on string theory, black holes, and quantum gravity.

All section

All section