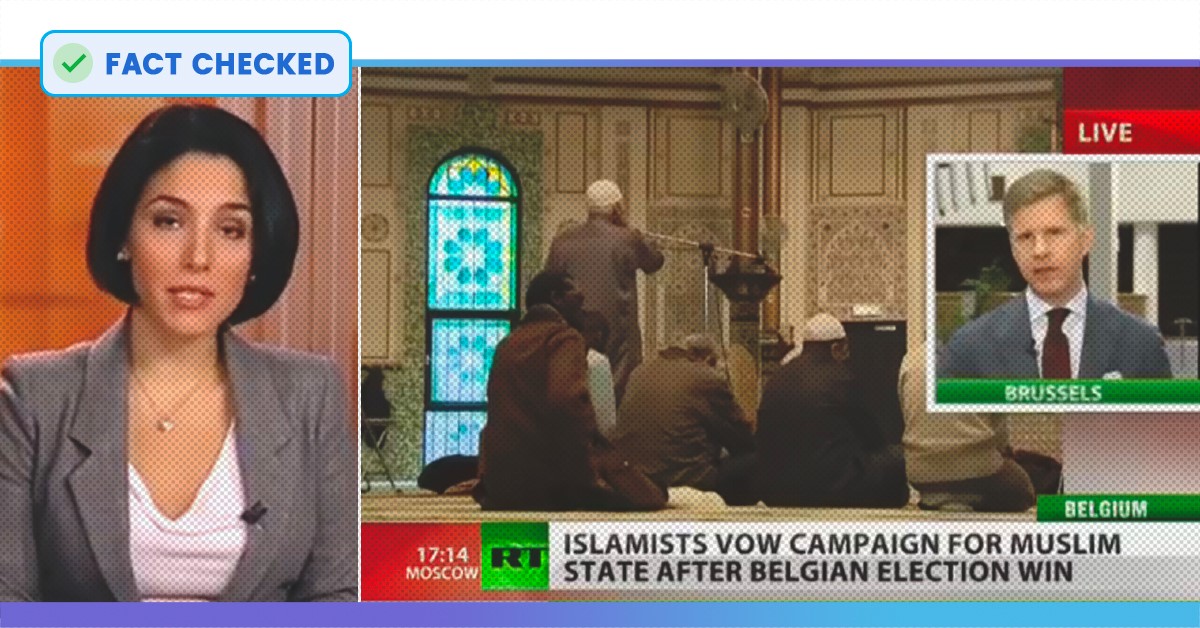

An old news bulletin from 2012 ran by the famous Russian news channel Russia Today (RT) about the ‘Islam Party’ of Belgium (Belgian), claiming to take over the country and bring Sharia law to make it an Islamic country is going viral. It is being claimed that the video is a recent one, which is absolutely false.

Mr Mahesh Hegde, the founding member of Postcard, a platform notorious for spreading fake news, shared this 2:15 minute long video with a false context. In an attempt to spread fear and Islamophobia among common people, Hegde said that the same is going to happen in India soon.

After winning elections,

Muslim parties demanding to declare Belgium as Islamic country.

Huge protests have already started

This is what going to happen soon in india also

All the best to my beloved so called "SECULAR" brothers and sisters pic.twitter.com/6CQZgP1FYh— Mahesh Vikram Hegde (@mvmeet) November 2, 2019

After winning elections in Belgian, Muslim parties demanding to declare Belgium as Islamic country. Huge protests have already started. If we don’t learn from their experience we are going to face the same soon. pic.twitter.com/CE6RW83wzi

— Ajit Doval Fan (@AjitKDoval_FAN) November 3, 2019

This video also went viral on Facebook as well.

After winning elections, Muslim parties demanding to declare Belgium as Islamic country. Huge protests have already startedThis is what going to happen soon in india alsoAll the best to my beloved so called "SECULAR" brothers and sisters.

Hindus of India ಅವರಿಂದ ಈ ದಿನದಂದು ಪೋಸ್ಟ್ ಮಾಡಲಾಗಿದೆ ಶನಿವಾರ, ನವೆಂಬರ್ 2, 2019

Belgian Muslim State? Islamists vow campaign after election win

A Muslim party in Belgium says it’s preparing to campaign for setting up an Islamic state there. Two candidates from the newly-established Islam party won seats in a recent municipal election.After winning elections, Muslim parties demanding to declare Belgium as Islamic country.They want the churches to be shut/converted to mosques.Huge protests have already started. Is this what is going to happen soon everywhere?

Invaluable Christian Messages ಅವರಿಂದ ಈ ದಿನದಂದು ಪೋಸ್ಟ್ ಮಾಡಲಾಗಿದೆ ಮಂಗಳವಾರ, ಜೂನ್ 18, 2019

Fact Check

On searching on YouTube about Belgium Islamic party and Belgium Municipal Election, we came across an old video uploaded by Russia Today on their own account. The video is the same as the one that’s going viral as new. It is titled ‘Belgian Muslim State? Islamists vow campaign after election win’ and is uploaded by Russia Times on their own YouTube channel, seven years ago, on October 30, 2012.

In the video, one can see then Belgium Euro MP, Mr Philip Claeys analyzing the situation and the reason behind this demand put forward by the Islamists of Belgium after the election win in 2012.

The ‘Islam Party’ of Belgium was established in the year 2012. After winning two seats in 2012 municipal elections, they vowed to implement the Sharia law, as per as the particular report of Russia Times of 2012. The ‘Islam Party’ back in 2012 won two seats but failed to win a single seat in the election of 2018.

The above video has been fact-checked by Alt News & Boom Live

Also Read: Islamic State Chief Resurfaces After 5 Years, Claims Sri Lankan Blasts Were Revenge For Baghouz