A Page From The Past: All You Need To Know About Emergency Imposed By Indira Gandhi Government

30 Aug 2016 6:36 AM GMT

Never in the history of independent India have we faced such a constitutional crisis as during the 21 month period in 1975-1977, when a state of emergency was declared across the country. It was officially issued by President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed on the recommendation of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. It was done under Article 352 of the Indian Constitution because of ‘internal disturbance’. The Emergency, as the period is commonly known in India, lasted from 25 June 1975 until its withdrawal on 21 March 1977.

Years preceding the emergency

The social and economic condition of the country was in bad shape during 1972-1975. Although the win over Pakistan in the war brought much praise for Indira Gandhi from the common man, the war and the eight million refugees from Bangladesh had put a heavy strain on our economy. After the war the U.S government stopped all aid to India and the oil prices also increased manifold in the international market. This led to a general increase in prices of commodities (23% in 1973 and 30% in 1974). Such a persistently high level of inflation was causing great distress to the people. Moreover, industrial growth was low and unemployment was high.

The government’s move to freeze the salaries of its employees to reduce its spending further led to resentment amongst the government employees. Monsoons failed in 1972-1973, resulting in the food grain output declining by 8%. There was a general atmosphere of dissatisfaction with the prevailing economic situation all over the country.

Protests in Northern India

The protests in Gujarat and Bihar, led by students, played a pivotal role in galvanising a nationwide opinion against Congress and the Prime Minister. In January 1974 students in Gujarat started protesting against rising prices of food grains and other essential commodities and corruption in the state government. The protests became widespread with major opposition parties (including Moraji Desai, a prominent political leader and a rival of Indira Gandhi when he was in the Congress) joining it, leading to the imposition of President’s rule in the state. Demands for fresh elections became intense. Subsequently, elections were held in Gujarat in June 1975, which the Congress lost.

Students in Bihar came together in march 1974 to protest against rising prices, food scarcity, unemployment and corruption. As the movement gained strength, they invited Jayaprakash Narayan (JP), who had given up active politics and was involved in social work, to lead it. He accepted it and took the movement to the national level.

Jayaprakash Narayan demanded the dismissal of the Congress government in Bihar and gave a call for total revolution in the social, economic and political spheres of the society. The movement gained momentum with a series of strikes and protests. The government, however, refused to resign.

Jayaprakash led a massive political rally in Delhi’s Ramlila grounds on 25 June 1975, where he announced a nationwide Satyagraha for Indira Gandhi’s resignation and asked the army, police and government employees not to obey ‘illegal and immoral orders’. The government perceived this as an incitement and felt that it would bring all government machinery to a standstill.

Alongside the agitation led by Jayaprakash Narayan, the employees of the Railways gave a call for a nationwide strike, led by George Fernandes.

Disqualification of Indira Gandhi as an MP

In the 1971 Parliamentary elections, Indira Gandhi defeated Raj Narain from the Rae Bareli constituency. Subsequently, Raj Narain filed a petition In the Allahabad High Court accusing Indira Gandhi of electoral malpractices, bribing voters and misuse of government machinery. Indira Gandhi was also cross-examined in the High Court which was the first such instance for an Indian Prime Minister. On 12 June 1975, Justice Jagmohanlal Sinha found the prime minister guilty of misuse of government machinery during her election campaign and declared her election null and void and also barred her from contesting any election for the next six years. The court, however, gave the Congress twenty days to make arrangements to replace Indira as the PM. A leading newspaper described it as ‘firing the Prime Minister for a traffic ticket’.

Indira Gandhi challenged this verdict in the Supreme Court. On June 24, the Supreme Court granted her a partial stay on the High Court order – till her appeal was decided, she could remain an MP but could not take part in the proceedings of the Lok Sabha.

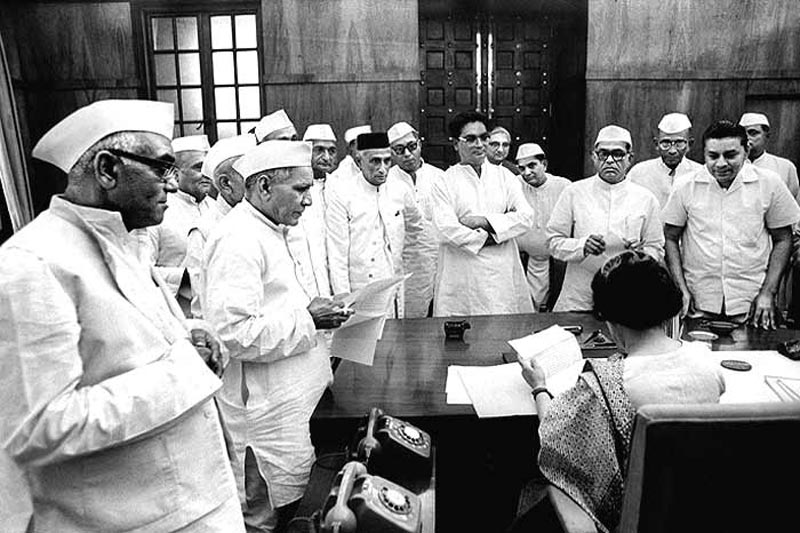

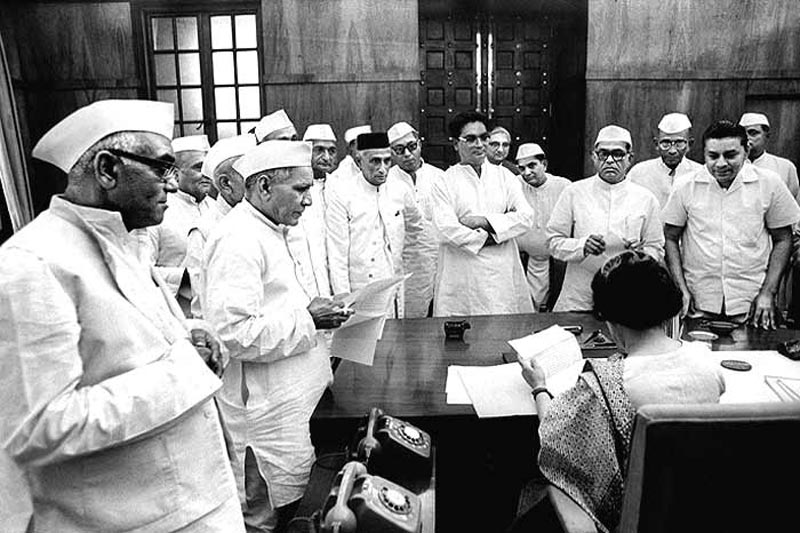

Proclamation of Emergency

The government responded to the massive strike on June 25, 1975 by declaring a state of emergency that night itself, saying that there was a threat of internal disturbances and that a grave crisis had arisen which made the proclamation necessary. PM Indira Gandhi recommended to the President to proclaim a state of emergency, and he did so immediately. After midnight, the electricity to all the major newspaper offices was disconnected, and was restored only two to three days later after the censorship apparatus had been set up. Early morning, on 26, a large number of opposition leaders and workers were arrested. The Union Cabinet was only informed about it at a special meeting at 6 a.m, after all this was over.

What occurred during the emergency?

It is clear from the words of article 352 that the Emergency is seen as an extraordinary condition, where normal democracy cannot function. Some of the exceptions occurred during the period were-

a) The federal distribution of powers no longer remained in order. All the powers were concentrated in the hands of the Union government.

b) Government gets to restrict or limit any or all of the fundamental citizens during the emergency, and it made use of this power quite extensively. This included the right of citizens to move the Court for restoring their fundamental rights.

c) All newspapers needed to get prior approval for all their materials to be published. This is known press censorship.

d) Apprehending social and communal disharmony, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and Jamait-e-Islami were banned. Protests, strikes and public agitations were also disallowed.

Excesses during the Emergency

The government made blatant and extensive use of its power of preventive detention. People were arrested and detained only on the apprehension that they may commit an offense. Negating the judgment of several High Courts, the Supreme Court in April 1976 gave a judgment upholding the constitutional validity of such detentions during emergency. The Shah Commission estimated that nearly 1,11,000 people were arrested under preventive detention laws. Torture in police custody and custodial deaths also occurred during Emergency.

Sanjay Gandhi, the Prime Minister’s younger son, did not hold any official position at the time. Yet, he gained control over the administration and allegedly interfered in the functioning of the government. His role in the demolitions and forced sterilisation in Delhi became very controversial.

The Constitution was amended in an autocratic manner, particularly in the 42nd amendment, as the government enjoyed a huge majority in parliament. In the background of the Allahabad High Court verdict, an amendment was made declaring that elections of Prime Minister, President and Vice-President could not be challenged in the Court.

Acts of dissent and resistance did happen during the emergency, but were few. Newspapers like the Indian Express and the Statesman protested against censorship by leaving blank spaces where news items had been censored.

Was the Emergency justified?

The emergency was declared stating the security of India was threatened due to internal disturbances.

In an AIR broadcast on 26 June 1975, Indira Gandhi said– In the name of democracy it has been sought to negate the very functioning of democracy. Duly elected governments have not been allowed to function. Agitations have surcharged the atmosphere, leading to violent incidents. …Certain persons have gone to the length of inciting our armed forces to mutiny and our police to rebel. The forces of disintegration are in full play and communal passions are being aroused, threatening our unity. How can any Government worth the name stand by and allow the country’s stability to be imperilled? The actions of a few are endangering the rights of the vast majority.

On the other hand, JP and other opposition leaders believed that in a democracy, people had the right to publicly protest against the government.

The Bihar and Gujarat movements were largely peaceful and non-violent. Moreover, even if some undue incidents happened, the government had enough routine powers to control them. There was simply no need to resort to such an extraordinary measure for that. In fact, the threat was not to the unity and integrity of the country but to the Congress government and to the prime minister herself.

The End of Emergency and After

After 18 months of emergency, in January 1977, the government finally decided to hold election in March 1977. Accordingly, all the leaders and activists were released from jails. Although this gave the opposition very little time, it quickly united to form a new party, Janata Party, under the leadership of JP.

Highlighting the dictatorial character and the various excesses committed during the emergency, the Janata Party turned the elections into a referendum on the experience of the emergency, at least in the North India. The public perception was very much against the Congress and the formation of Janata Party ensured that the non-Congress votes would not be divided.

For the first time since independence, the Congress party was defeated in the Lok Sabha elections. The Congress could win only 154 seats in the Lok Sabha, whereas the Janata Part got 295 seats (330, along with its allies).

Indira Gandhi was defeated from Rae Bareli, as was her son Sanjay Gandhi from Amethi.

An important constitutional amendment done by the new government was substituting ‘armed rebellion’ in place of ‘internal disturbance’ and making it necessary that the advice to the President to proclaim emergency must be given in writing by the Council of Ministers.

All section

All section