The day for ragpicker families near Bhopal’s railway lines began at 4 a.m., sacks on their backs, children trailing beside them, and an entire childhood slipping past between garbage heaps and railway tracks. In that harsh routine, a small, audacious idea took shape: what if the platform itself could become a classroom, and what if these children, invisible to the city, could grow up as rights-holders, not victims?

That question became the seed of AARAMBH – Education & Community Development Society, co-founded and led by social workers Archana Sahay and Anup Sahay, transforming vulnerability into empowerment across Madhya Pradesh.

The Beginning: A Personal Resolve Becomes a Collective Journey

For Archana Sahay, Director of AARAMBH, the decision to work with children was not an abstract choice but a response to lived trauma. As a social work student in Bhopal during the gas tragedy, she witnessed firsthand how disasters crush children first and hardest, leaving lasting scars on families and communities. “I always had a passion to work with children,” she recalls, her voice carrying the weight of that formative experience.

After completing their MSW in the late 1980s, Archana and her batchmate Anup began their careers in Delhi with child-focused organisations. Anup immersed himself in work directly supporting children’s welfare. Archana later engaged deeply with emerging child rights efforts, including the dissemination of UNCRC which was ratified by India on 11th December 1992. “When we finished our MSW, we got a chance to work with international organizations in New Delhi,” she says, crediting those years with sharpening their vision.

When they returned to Bhopal in 1992, they immediately took up roles keeping them close to vulnerable children. Anup secured an assignment with the state government on non-formal education, while Archana joined SOS Children’s Village, a newly launched initiative specifically for gas-affected children. “Bhopal brought us back. And we thought that we should do something of our own,” she tells The Logical Indian.

Laying the Foundation: Vision Before Funding

From 1992 to 1997, AARAMBH existed more as a dedicated practice than a formal project. Archana and Anup balanced full-time jobs while pouring their free hours into street children, gas-affected families, and platform dwellers. They sat with them on the ground, listened intently to their stories, and organized small educational activities, all with no external funding, relying solely on personal conviction and community goodwill.

In parallel, they meticulously built the organisational infrastructure: crafting a clear vision and mission, securing essential legal registrations including FCRA , 80 G and 12A, and refining objectives for sustainability. “From 1992 till 1997, we did our base work, before entering into any project,” Archana explains.

At the heart of this foundation lay the UNCRC, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), adopted by the UN General Assembly on November 20, 1989, as the most comprehensive and widely ratified human rights treaty in history, ratified by India in 1992. This landmark document contains 54 articles that establish civil, political, economic, social, health, and cultural rights for every child under 18—ranging from the right to survival and development, protection from violence, abuse and exploitation, access to education and healthcare, to the right to be heard and participate in matters affecting their lives.

“Whatever is written in this document, all the 54 rights should be received by all children,” she affirms.

Platform Classrooms and Ownership: The First Centres

The ragpicker community near the Bhopal railway station became AARAMBH’s proving ground. These migrant families from rural Maharashtra structured their lives around dawn-to-dusk ragpicking, with children inevitably pulled into the grind. AARAMBH responded by establishing informal learning centres right on the platforms where these children lived and worked.

With zero budget, creativity ruled. “Someone gave a sack. Someone gave a sheet, We prepared the centre like this,” Archana says. A determined local girl in Class 12, living with relatives and needing pocket money, was trained to lead the centre after her own school hours. Slowly but steadily, children made the leap to formal schooling, marking the first tangible victories of community-owned education.

Childline 1098: When the Phone Became a Lifeline

A pivotal moment arrived in 1998 when Archana, sponsored by UNICEF, attended a Tata Institute workshop on Childline 1098, a groundbreaking 24/7 emergency helpline for children in distress. The concept resonated immediately. “This is exactly what I was looking for,” she thought, envisioning a direct channel for street children craving both freedom and fundamental protections.

With backing from UNICEF, police, and government, Childline launched from AARAMBH’s modest office on 10 August 1998 in Bhopal. It became the first City in Madhya Pradesh and 9th City in the country to start the helpline service. In those early months, Archana, Anup, and a skeleton team handled night shifts themselves. “When the childline came, reaching out to the most vulnerable children became easy,” transforming crisis response into a daily reality and expanding AARAMBH’s reach exponentially.

The organisation with all dedicated and committed team ran the project for 25 years till the year 2023, before the Government took over the services all over the country to be run now by Government rather than NGO’s.

Roads, Drains, and RTI: Children as Changemakers

As Childline cases multiplied across the communities,the project ran for street children in 15 Communities by AARAMBH , stark infrastructure deficits emerged, overflowing drains soiling school uniforms during monsoons, girls missing classes to fetch erratic tap water, open defecation exposing them to assault.

AARAMBH’s team pivoted to empowerment through the Right to Information (RTI) Act, conducting intensive 15-day workshops and theatre training for youth leaders. “We built the capacity of the children, they wrote applications, and went to Nagar Nigam,” she recounts. When officials dismissed the young filers, the children countered: no age bar exists in RTI law.

Entire communities rallied behind them, securing paved roads, repaired drains, and functioning streetlights. “We tried to see the change through the children, always,” proving that empowered youth could reshape their environments.

Negotiating Resistance: Faith, Gender, and Trust

Entry into new communities demanded nuance. AARAMBH sought trusted local voices, strong mothers, respected elders, faith leaders; over political figures. When proposing reproductive health camps in conservative Muslim areas, a Maulvi initially objected. “We talked to him first,” Archana shares, promising transparency. Post-camp findings revealing reproductive health issues among women converted skepticism to support.

In Dewas district’s Sonkatch block, they engaged the Nihal community’s headman, historically tied to bonded labour, facilitating access to housing schemes and schooling that broke generational cycles and earned the headman’s advocacy with district authorities.

From Water to Eye Health: Rights in Everyday Life

The communities revealed two distinct yet compounding crises: relentless water queues that forced children, particularly girls, to skip school and drop out entirely, and sanitation gaps, marked by absent toilets- that exposed them to violence, infections, and indignity, further disrupting education. Alongside these, poor eyesight went unaddressed, with girls specifically pulled from school because they “couldn’t see the blackboard,” deemed unfit for class despite their potential.

AARAMBH tackled eyesight separately through Amrita Drishti. Partnering with Sightsavers, they launched community vision centres in slum clusters. These centres served as accessible hubs where local vision ambassadors, trained teachers, parents, and health workers conducted initial screenings and educated families on eye health. Over time, the initiative evolved and the government took ownership.

Then AARAMBH, integrated mobile eye unit, expanding reach to remote areas with advanced equipment for detecting cataracts, diabetic retinopathy, refractive errors, and other conditions. The program specifically prioritized those girls, ensuring they received free glasses, corrective care, and follow-up services, restoring their vision, confidence, and attendance to break barriers to education. Archana asserts, “Clear vision should be seen as a right,” embedding this vision intervention into a rights-based framework. Complementing it, community-led toilet initiatives, run by women in a hilly area, empowered locals to build and maintain sanitation facilities tailored to rugged terrain, charging a 50 rupees fine for throwing garbage.

This restored sustainability while providing safe, private spaces that slashed violence risks, curbed infections, and restored dignity for girls. These women-led committees not only constructed durable toilets suited to steep slopes but also managed upkeep through community contributions, fostering ownership and long-term hygiene habits. Water access programs paired this by installing safe hydration points at schools, slashing dropout queues and health absences. Archana notes, “When girls have toilets and water nearby, they stay in school, simple infrastructure unlocks their future,” ensuring these efforts keep children confident, healthy, and learning.

Help Desks, Schools, and Police: Systemic Partnerships

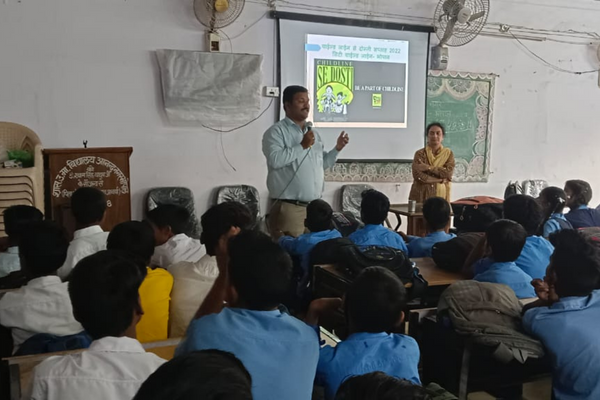

To demystify government schemes, AARAMBH created youth-led help desks tackling Aadhaar updates, Samagra IDs, and bank linkages, barriers blocking families from entitlements. In schools, sessions pair facilitators with uniformed police, humanizing authority and building early familiarity with law enforcement as allies rather than threats. “Children are happy to see the uniform,” Archana notes, highlighting how this exposure shifts perceptions from fear to trust, encouraging kids to view police as approachable protectors.

Community policing partnerships with Police Head Quarters, Bhopal take this further through intensive 15-20 day SRIJAN camps initiated by Dr.Vineet Kapoor, DIG Community Policing and PSO to DGP designed for vulnerable youth in high-risk areas, accommodating 50-60 students per batch. These camps blend physical empowerment, teaching martial arts for self-defense by Police trainers; with critical awareness sessions on POCSO (Protection of Children from Sexual Offences) laws, spotting cybercrime tactics like online grooming, and practical traffic safety skills such as safe road crossing and helmet use etc. by different resource persons.

Facilitated by Police trained officers alongside AARAMBH mentors, the camps include role-playing scenarios, group discussions, and real-world simulations to instill confidence and vigilance. Archana emphasizes that “these camps bridge the trust gap, turning potential conflicts into lifelong partnerships,” while adding, “Safety walks and increased Police patrolling with children makes streets safer, kids spot dangers we miss, and police gain eyes everywhere.” Participating children report feeling safer and more empowered, while police gain insights into community needs, fostering sustained collaboration that reduces crime and enhances child protection.

POCSO and Missing Girls: Tough Work Ahead

AARAMBH now provides POCSO support persons, accompanying survivors from FIR to conviction; a grueling journey ,Madhya Pradesh’s missing girls crisis, acknowledged by senior police, demands urgent focus. “We need to work on prevention, with men and boys,” Archana emphasizes, targeting consent education and rural outreach where 80% of youth cases involve mutual relationships misconstrued as assault, building safer ecosystems through inclusion rather than isolation.

Walking Forward: Helping People Help Themselves

Political shifts come and go, but grassroots realities, poverty, health gaps, awareness deficits, persist. “People change, but issues are the same,” Archana observes. Her timeless principle, “Help them to help themselves,” drives capacity-building across modules: parenting, leadership, RTI, community policing. The vision is exit strategies yielding ownership: trained youth sustaining help desks, women managing sanitation, panchayats self-monitoring child protection. “We want to see who we have prepared, move to another area which is more vulnerable. There is no shortage of work,” she plans, eyeing three-year expansion into missing children while deepening rural prevention.

In her conversation with The Logical Indian, Archana’s resolve radiates undimmed after decades. “More is always less, but when people see this as their own issue and solve it themselves, sustainability lasts; even if outsiders come and go.” AARAMBH endures not as perpetual intervention but as catalyst, leaving behind empowered communities carrying the torch.

Under Archana and Anup Sahay’s steady leadership, AARAMBH remains a living beginning; a continuous, evolving commitment turning abstract global rights into concrete Bhopal platforms, Dewas panchayats, and Madhya Pradesh futures where every child claims their full humanity.

The Logical Indian’s Perspective

At The Logical Indian, we celebrate changemakers like Archana and Anup Sahay whose grassroots work transforms lives, from turning railway platforms into classrooms, water taps into school attendance, and global rights into local realities, believing that highlighting such stories inspires communities to build sustainable change.

If you’d like us to feature your story, please write to us at csr@5w1h.media

Also Read: People of Purpose: From Grassroots to Runa Pathak’s Impact Leadership at Jubilant FoodWorks Ltd