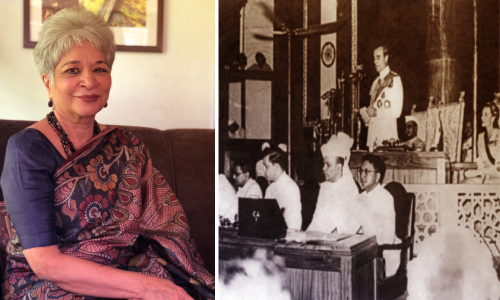

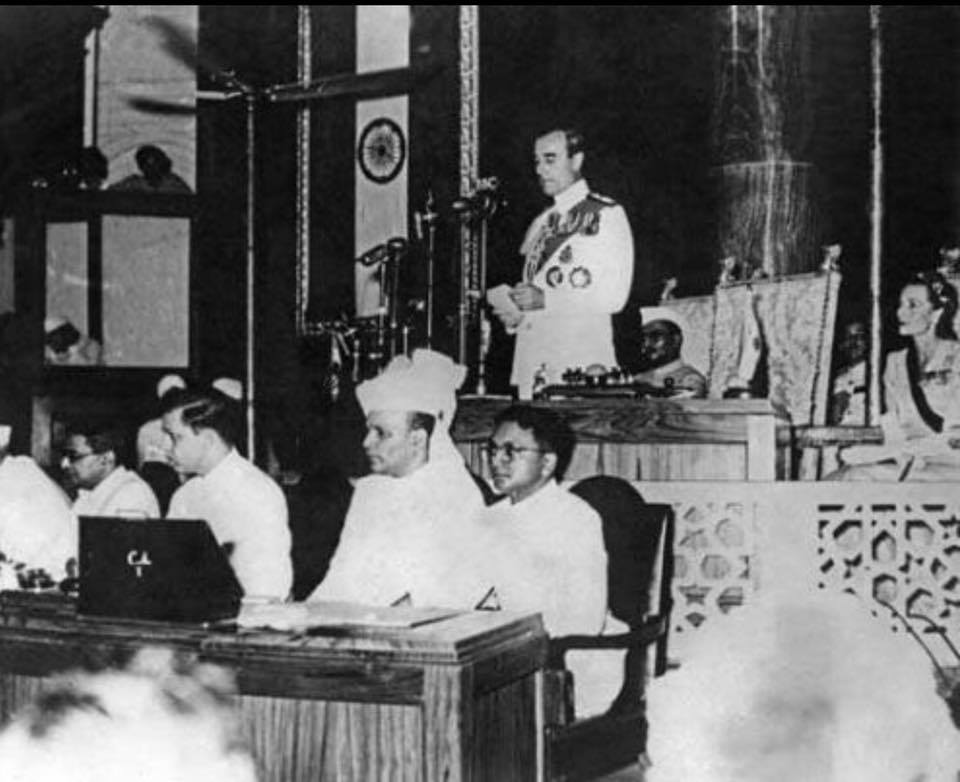

I am one of Midnights Children, 1947 born, and as old as independent India. The picture below is of my father, wearing his towering cream saafa, at the Constituent Assembly as Mountbatten handed over the power – what stirring times.

The country has changed as much as I have myself in these 73 years – in thought, in ways of being, in appearance, in style, in politics. Even in shape, as Goa and Sikkim became a part of India, and China continues to take bites out of it. The once-mighty Indian National Congress, then almost synonymous with the country, is a sad, sinking ship, unwilling to introspect and change. The BJP, nonexistent then, reigns supreme.

The biggest changes, of course, are material ones. Even 45 years ago, when I first began working with craftspeople, rural India was in a time-warp, treating us city types as coming from another planet. People lived in thatched mud huts, without water, electricity or sanitation, and had little contact with the outside world, each region with its own distinctive social mores and culture. Nor had television yet shown them what that outside world was like, raising their aspirations but also their sense of being unfairly disadvantaged.

Today a majority do have semi-pucca houses and have gas cylinders, toilets, power connections. They travel all over India, whether for work or to sell their wares. They have cell phones to chat with one another, trawl the internet, access TikTok. The rural/urban divide still remains though, and in many ways, the emotional disconnect between the ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’ has increased.

Even the privileged upper-middle-class led comparatively simple, austere lives in those early days. Gandhism and Swadeshi were still living concepts. Liberalisation and the shiny allure of international brands were a long way away. We went on picnics and treks not trips to Switzerland or Bali; driblets of foreign exchange were issued to only an entitled few. No one drank wine or Scotch; people swam and played tennis and badminton, no one went to gyms.

Everyone cycled to school, and most people, whether maharajas, industrialists, or the Prime Minister, drove the same Ambassador cars. Power-cuts were the norm, and air-conditioning in a few fancy homes only started in the mid-60s. A long-distance phone call took days to connect, a telegram maybe 24 hours. The few airports were cosy snug places, with stuffed sofas and artificial flowers in Moradabad brass vases – one generally knew most of the people flying. The idea of buying a bottle of water would have made people laugh! We were the generation that hoarded biscuit tins and carrier bags; that gifted our friends home-made jam but asked for the bottles back.

When I wrote on consumerism recently and thought of the various gadgets and gizmos that are now an indispensable part of my life, I felt a little sheepish. I listed all the electronic things I use that one didn’t dream of in the 50s and 60s. My iPad, iPhone and iPod, my laptop, my Kindle, my scanner and printer, my microwave, my mixie, my music system, my TV, my AirFryer, my Instapot, my Soup Maker, my vacuum cleaner, my washing machine, my hairdryer, my air purifier, and now my sanitiser box! Today, built-in obsolescence is a part of life, and one changes cars and phones every few years.

My grandmother had the same Morris car and General Electric refrigerator from before I was born to her death 45 years later. Ovens were little tin boxes we put on top of the stove. And our khansamas made light as air soufflés without electric beaters! It is the cooks now who are in short supply.

Feminism came to India as a wave in the late 60s early 70s – mostly through educated English-speaking women reading Germaine Greer, Kate Millett, Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem. I read their books avidly but felt I already knew all that! The women in my family had been encouraged for the past three generations to be independent, free-thinking, with lives of their own; many remaining unmarried (as I have). I lived on my own in my Defence Colony.

I’d never experienced the tyranny of male patriarchy. In one’s 20s one sees the world through one’s own self-centred prism. It took working with women in rural India to make me realise that the whole point of independence is to enable others to have it as well.

Regretfully, all these years on, I personally don’t feel that much has changed for millions of Indian women in the lower rungs of society, except that they now have the additional burden of also being wage-earners. Certainly, there were more women in Parliament then than now!

Secularism was not an outmoded word then. People seemed to relish the multilayered multiplicity of Indian society and culture. Despite the raw wounds of Partition, there was nostalgia for a time of tehzeeb and biradari when different communities lived side by side, studying, working and celebrating together. Indians were still bonded together by the joint struggle for Independence and the excitement and challenges of shaping a new country.

There were still so many British expats and Anglo Indians, staying on in a country they loved. So many more Christians and Parsis and Jews. Freedom of speech was alive and vigorous. Pandit Nehru relished and collected the often cuttingly satirical cartoons Laxman and Shanker made of him. I wonder what he’d have thought of a cartoonist being arrested for sedition. In these 73 years, travel and the Internet have made the world much more accessible to us, but, curiously, national mindsets worldwide have become more insular and humourless.

As for craft, the sector where I work, it wasn’t a separate little box then, uninvested in and the economics of it mostly ignored; only taken out when talking of tourism, heritage, and aesthetic. Everyone wore khadi and handlooms and used handmade Indian things; alternatives didn’t exist. I am all for global markets, but doors must open both ways. I am happy at the recent revival in interest in sarees and other traditional textiles, and natural green products, but it is still slightly self-conscious niche patronage, while sadly weavers and craftspeople are still not regarded on par with other professionals, socially or economically.

As we sit, still semi housebound, awaiting the arrival of that mysterious post-COVID world, one wonders what this coming year will bring. Will India in August 2021 have changed all over again?

If you too have an inspiring story to tell the world, send us your story at

mystory@thelogicalindian.com