The Supreme Court of India has ruled that groping a girl and untying her pyjama string constitutes an “attempt to rape”, setting aside a controversial judgment by the Allahabad High Court that had earlier termed similar actions as mere “preparation” to commit rape a finding that drew national outrage and raised serious questions about judicial sensitivity in sexual offence cases.

The top court’s decision also calls for broader reforms to ensure empathy and compassion in handling such matters across the judiciary.

Landmark Verdict Restores Attempt to Rape Charges

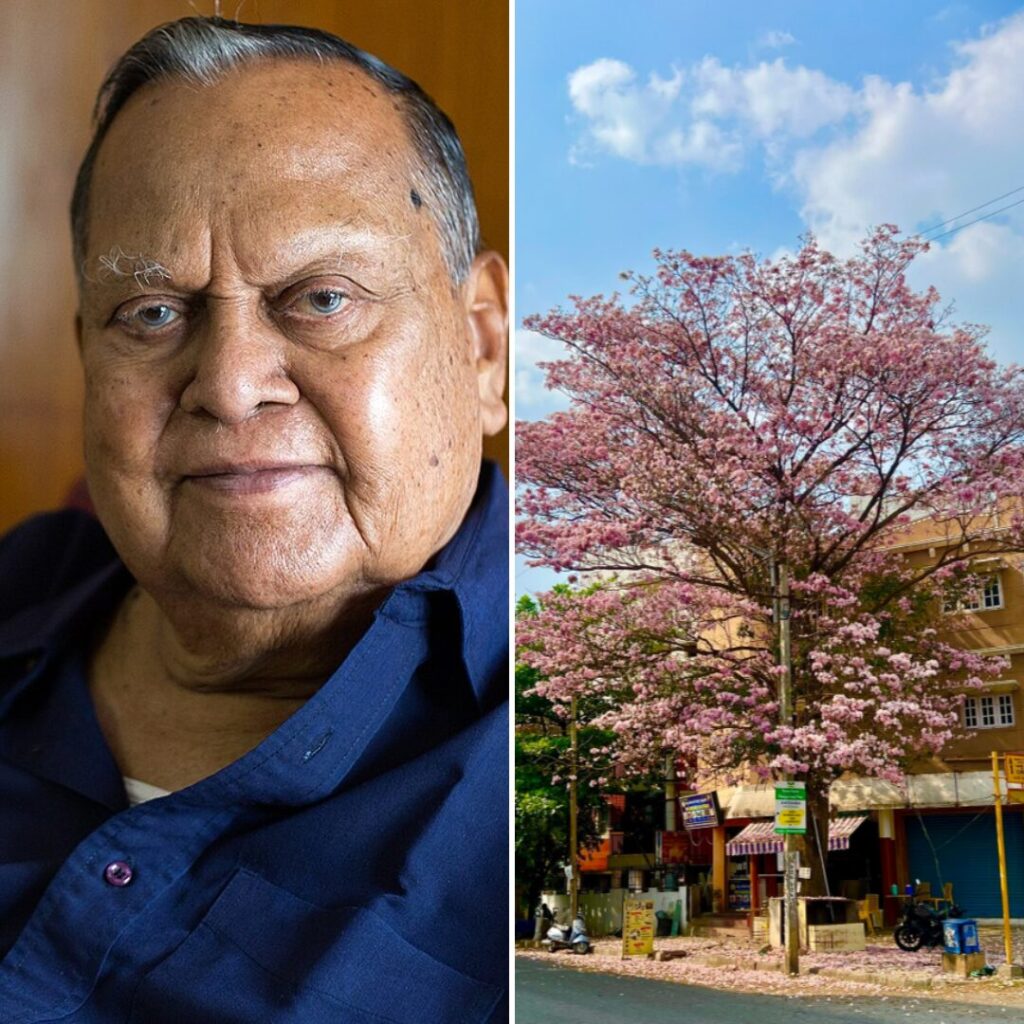

In a pivotal decision delivered on 10 February 2026, a three-judge Bench led by Chief Justice of India Surya Kant, alongside Justices Joymalya Bagchi and NV Anjaria, quashed the March 2025 ruling of the Allahabad High Court that had downgraded serious charges to lesser offences.

The high court had earlier held that actions including grabbing a minor girl’s breasts, breaking the string of her pyjama, and trying to drag her beneath a culvert did not amount to an attempt to rape.

Restoring the original summons order issued by the Special Judge (POCSO), Kasganj, the Supreme Court underscored that the accused persons had gone well beyond mere preparation and crossed into the realm of an actionable attempt to commit rape under Section 376 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) read with Section 18 of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act.

The Bench said that a “bare perusal” of the allegations left no “modicum of doubt” about the pre-determined intent of the accused.

The order also clarified that its observations were prima facie that is, based on the facts presented and for the purpose of framing charges and did not imply any opinion on the actual guilt or innocence of the accused in the ongoing trial.

Case Facts and Initial High Court Ruling

The case stems from an incident on 10 November 2021, when the mother of a 14-year-old girl filed a complaint alleging that the accused identified as Pawan, Akash and Ashok, had given her daughter a lift on a motorcycle when she was returning home.

According to the prosecution, the trio stopped along the way, began groping the girl, pulled the string of her pyjama, and attempted to forcibly take her beneath a nearby culvert. The accused fled after passers-by intervened.

Initially, a trial court had found sufficient grounds to summon the accused on charges of rape and attempted penetrative assault, but the Allahabad High Court in March 2025 modified these charges, observing that the actions did not fulfil the legal threshold for an attempt to rape since there was “no direct evidence of penetration or completed disrobement,” and instead fell under lesser offences like assault with intent to disrobe and aggravated sexual assault under the POCSO Act.

That ruling drew widespread criticism for its legal reasoning, with critics saying it unjustifiably narrowed the interpretation of what constitutes an attempt to rape, particularly in the context of child sexual assault.

Civil society, legal experts and women’s rights groups had raised concerns that such a judgment could set a dangerous precedent and undermine protections meant to safeguard vulnerable victims.

SC’s Legal Reasoning and Call for Judicial Sensitivity

In reversing the high court’s view, the Supreme Court emphasised that attempt begins where preparation ends and in this case, the allegations showed more than mere preparation.

According to the Bench, acts like groping, forcefully pulling a garment string, and attempting to seize the victim signify a decisive move towards the crime that cannot be dismissed as preparatory.

The apex court also noted that the high court’s interpretation showed a “patently erroneous application of settled principles of criminal jurisprudence” and lacked an understanding of ground realities faced by survivors, especially minors.

In a significant extension of its order, the Supreme Court has requested the National Judicial Academy (NJA), Bhopal, to set up a committee of experts, including former judges, to draft comprehensive, accessible guidelines aimed at fostering sensitivity and compassion in the judiciary’s approach to sexual offence cases.

These draft norms are expected to serve as a framework for training judges and court staff across India and are to be submitted preferably within three months.

The Bench stressed that mere application of technical legal principles is insufficient and that the judiciary must balance the law with an understanding of the trauma, vulnerabilities and lived experiences of victims who seek justice.

Reactions

Legal commentators have broadly welcomed the Supreme Court’s decision as a necessary correction to a prior judgment that many saw as misaligned with the intent of key criminal statutes designed to protect women and children.

Advocates said the ruling reasserts that intent and overt actions that clearly endanger bodily autonomy cannot be downplayed in judicial interpretation. Civil society activists also lauded the order’s broader push for judicial empathy and accountability.

Several women’s rights organisations have called the verdict a “victory for survivors,” noting that it sends a clear message that courts should recognise and respond robustly to the beginnings of sexual violence rather than diminish their gravity.

The Logical Indian’s Perspective

This ruling represents a crucial reaffirmation that the law must not only be technically correct but morally cognisant of the lived realities faced by victims of sexual violence.

When vulnerable survivors, especially minors, recount traumatic experiences, courts must interpret the law in ways that recognise intent and abusive conduct rather than allow narrow legalism to dilute accountability.

At a time when India strives to strengthen protections against sexual offences and align its justice system with principles of dignity, safety and empathy, the Supreme Court’s decision marks a step toward a more victim-centred jurisprudence.

Encouragingly, the call for judicial sensitivity training and guidelines reflects an understanding that legal outcomes are shaped not just by statutes but by the compassion and awareness with which judges and public institutions engage with survivors.