Video: Video Volunteers | Originally Published On Indiaspend | Video Volunteers & Prachi Salve

Last year, in eastern Bihar’s Phulvari Sharif, 24-year-old Masahun Khatun was five months pregnant when she fell in the front yard of her house. For the next three weeks, Masahun and her husband shuttled between government hospitals and private practitioners, spending over Rs 40,000 on healthcare, as they tried to get an abortion. Masahun did not survive and her husband, a daily-wage labourer, is struggling to raise their four kids. This is their story:

Almost a decade after the government launched the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY; Mothers’ Protection Programme) to reduce maternal and infant mortality by promoting institutional delivery, too many Indian mothers die of causes related to childbirth.

India’s MMR, or maternal mortality ratio (number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live child births), was 178 in 2010-12, worse than poorer countries such as Myanmar and Nepal, and about the same as Laos and Papua New Guinea, according to WHO data. As many as 50,000 pregnant women die every year in India during childbirth, according to this UN report.

The positive news is that the MMR has declined from 212 in 2007-09. Some states, such as Kerala (66), Tamil Nadu (90) and Maharashtra (87) have MMRs that match richer countries such as Brazil (69), Philippines (89) and Cuba (80).

Assam (328), Uttar Pradesh (292), Uttarakhand (292), Rajasthan (255), Odisha (235), Madhya Pradesh (230), Chhattisgarh (230), Bihar (219) and Jharkhand (219) have the eight worst maternal mortality rates in India. These numbers match some of the world’s poorest countries, such as Mauritania (320), Equatorial Guinea (290), Guyana (250), Djibouti (230) and Laos (220).

How the public healthcare system fails the poorest Indians

Three video stories by Video Volunteers (a global initiative that provides disadvantaged communities with story and data-gathering skills) reveal how difficult child birth is for the poor who have to depend on public-health services, and end up spending money that, in most cases, they do not have:

Below is the story of a pregnant woman in Bihar who was charged Rs 500 for cutting an umbilical cord. She also had to pay for painkillers needed before her delivery. Women in the village report that when they refused to pay, the ANMs refuse to attend to them. This is despite the government scheme (JSY) that hopes to reduce out-of-pocket expenditure for women below the poverty line by providing free ante-natal checkups, IFA (iron tablets) tablets, medicines, nutrition in health institutions, provision for blood transfusion, and transport to and from health centres.

This report below from Deogarh in western Jharkhand reveals corruption among auxiliary nurse mid-wives (ANMs) of a hospital who force pregnant women to pay for their services post-delivery.

As this report below details, pregnant women are forced to spend out of their pocket or are referred to other faraway health facilities because there aren’t enough medicines at a state-run health facility. Arti Devi was asked to deposit Rs 500 at a state-run health facility. It was a sum she could not afford, so was asked to go to another government hospital.

The JSY gives pregnant women–who deliver babies at home and live below the poverty line–Rs 500 as cash assistance, irrespective of the mother’s age and number of children, to give birth in a government or accredited private health facility. The scheme focuses on poor, pregnant women, with a special focus on states with low institutional delivery rates: Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Assam, Rajasthan, Odisha, and Jammu and Kashmir. The scheme also provides performance-based incentives to women health volunteers known as ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) to promote institutional deliveries.

Source: Ministry of Health; Note:*ASHA package of Rs. 600 in rural areas includes Rs 300 for ante-natal care and Rs 300 for institutional delivery; **ASHA package of Rs 400 in urban areas includes Rs 200 for ante-natal care and Rs 200 for institutional delivery.

The promise of direct transfers

A direct transfer of JSY benefits to the bank accounts of pregnant women started in 2013 and is now underway in 121 of 640 Indian districts.

JSY beneficiaries have increased from 0.7 million in 2005-06 to 10.4 million in 2014-15, an indicator that many pregnant women know of the scheme.

About 900,000 ASHAs get performance-based incentives to motivate pregnant women to give birth in health facilities. Of 10.4 million JSY beneficiaries in 2014-15, a large majority (nearly 87%) live in rural India.

State subsidies available, yet women end up paying

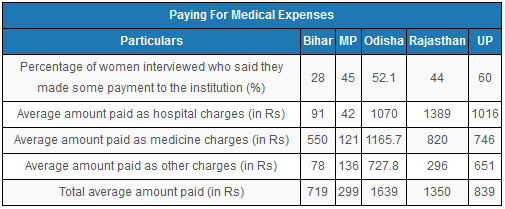

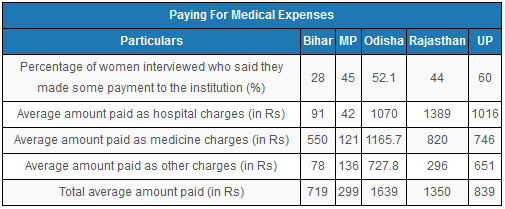

As many as 60% of women in Uttar Pradesh acknowledged paying money from their own pockets for certain services, according to an assessment of JSY conducted by United Nations Population Fund in Bihar, MP, Odisha, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh in 2012.

Source: United Nations Population Fund

Source: United Nations Population Fund

Women in Madhya Pradesh reported the lowest out-of-pocket expenditure, Rs 299, followed by Bihar with Rs 719.

Households spent an average of Rs 5,544 per childbirth in rural areas, according to a recent survey by the statistics ministry.

(This story is the result of a collaboration between Video Volunteers, a global initiative that provides disadvantaged communities with story and data-gathering skills, and IndiaSpend. Salve is a policy analyst with IndiaSpend.)

Source:

Source: