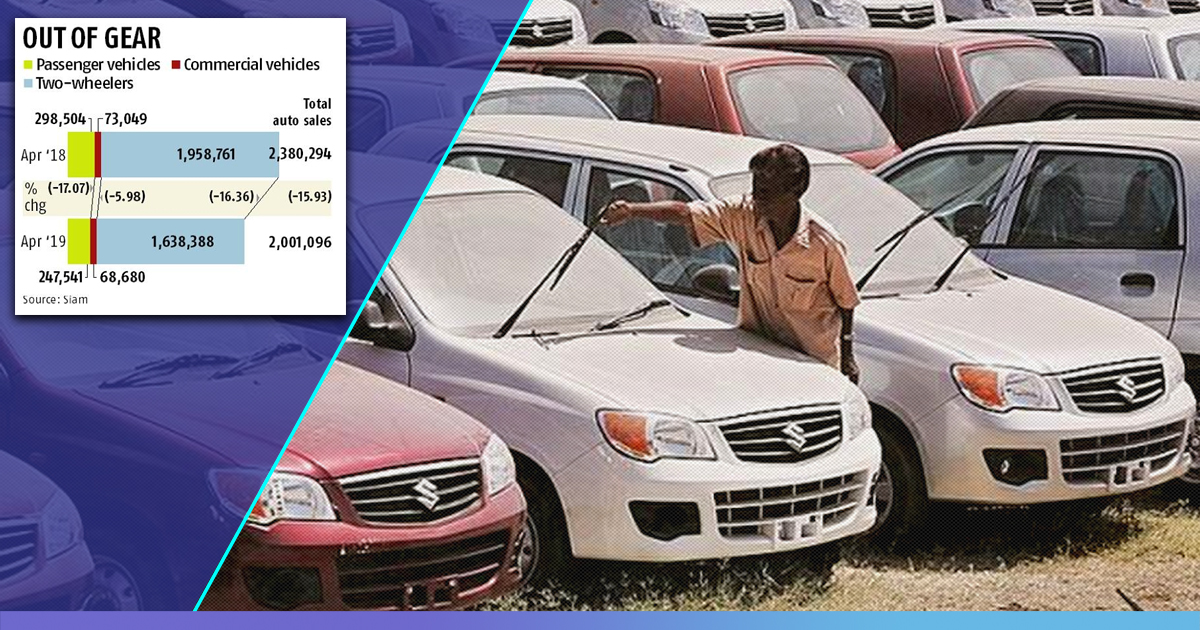

Between October and December 2018, India witnessed a decline in its economic growth as it fell to 6.55%, the slowest in six quarters. Growth rates of banks, FMCG companies, companies manufacturing cars, SUVs, two-wheelers and commercial vehicles have toppled to worrisome levels. While overall automobile sales dropped by 16%, car sales alone dropped by 20% and have hit the lowest since October 2011. Last year, India was the fastest growing aviation market but in March 2019, it recorded the slowest growth pace in almost six years. Hindustan Unilever Ltd., India’s largest maker of consumer staples, recently reported March quarter revenue growth of just 7%, the weakest in 18 months. Three years ago, Johnson & Johnson (J&J) built its largest biggest manufacturing plant in a rural area near Hyderabad. It was supposed to provide employment to nearly 1,500 people and bring development to the area. The 47-acre plant continues to stand idle hitherto owing to lack of demands.

Automobile companies on a rough ride

Maruti Suzuki, the grand old car manufacturing company has slashed down its production by 26.8%. Two-wheeler dealers are alarmed with vehicles staying in their inventories for 80-90 days against the normal level of 20-30 days. Nikunj Sanghi, director, international affairs at the Federation of Automobile Dealers Association, said it had been communicated to the manufacturers that inventories had reached alarming levels and they expected them to recalibrate their production over the next few months. Financial Express reports that major manufacturers like Hero MotoCorp, Honda Motorcycle and Scooter India (HMSI) and Royal Enfield have decided to cut back their monthly production by around 15 per cent from March till May 2019. Financial Express further reported that HMSI cut down its production in December as its inventory crossed 60 days. “Unlike nearly four lakh units produced every month, the company manufactured only 2.48 lakh units,” it said. Vishnu Mathur, Director General of SIAM (Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers ) said: “the sentiment in the market is not very good,” referring to the decline in automobiles sales.

Why is a decline in automobile sales worrisome?

Vivek Kaul, an economic analyst explained in his blog why growth in the automobile sector is reflective of our general economic growth. He writes, “That in February 2019, for the first time in four years, all the four economic indicators were in negative territory. This basically means that car sales, two-wheeler sales, tractor sales and commercial vehicles sales, all fell in comparison to the same period in 2018.” “Car sales are a very important economic indicator about how urban India feels about its economic prospects. After all, no one is forcing anyone to buy a car and given that if a consumer buys a car, he chooses to make a down payment and/or take on an EMI. This is only possible if the consumer is feeling positive about his future economic prospects,” says Kaul. The decline in car sales indicates the ominous feeling of the urban class regarding their future economic prospects.

Vivek Kaul

Kaul talks about the forward and backward linkages that car sales have. An increase in demand for cars will also mean an increase in demand for steel, rubber, paint, glass, batteries etc. These are backward linkages. A downfall of demand for cars will also affect service centres and bank loans. These are forward linkages. Car sales alone won’t be able to determine Urban India’s general economic prospect and thereby we also consider two-wheeler sales (Scooters are bought more in Urban India).

In February 2019, scooter sales fell by 12.14%, indicating that the population with the ability to buy a scooter or a two-wheeler also harbours an ominous feeling.

Autopunditz

To determine the economic prospects of rural India, we consider tractor sales. “The domestic tractor sales growth has been falling over the last few months. In fact, in February 2019, domestic tractor sales fell by 0.52%. The growth in agriculture, forestry and fishing, between October and December 2018, stood at 2.67%, the slowest in 11 quarters,” writes Kaul and further claims this to be an indication of the agricultural distress that prevails in the country.

Vivek Kaul

Commercial vehicles sales can be a brilliant indicator of infrastructural and industrial activity in the nation. The growth in the sales of commercial vehicles has been collapsing since last year. In February 2019, commercial vehicles sales fell by 0.58%. As per the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, “During October to December 2018, the new projects fell by 24.14%. Completed projects fell by 8.35% and the stalled projects went up by 246.89%.”

Vivek Kaul

FMCG sector’s growth faces heat too

Hindustan Unilever Limited, India’s leading FMCG brand, which witnessed double-digit growth in the last five quarters, said that its volume growth toppled to 7 per cent in the last quarter. The company warned that the daily consumer goods segment in India was “recession resistant … not recession proof.” Johnson & Johnson (J&J) built a manufacturing plant in a rural area near Hyderabad. And it’s supposedly J&J’s biggest manufacturing plant in India. Residents of the area were very hopeful to get employed in the plant as the plant promised nearly 1,500 jobs. The state government of Telangana also hoped that the plant will develop the rural area. It’s been nearly three years since the plant’s construction finished and hitherto the plant remains inactive. Two sources familiar with J&J’s operations in India and one state government official told Reuters production at the plant, at Penjerla in Telangana state, never began because of a slowing in the growth in demand for the products. One of them said that demand didn’t rise as expected because of two shock policy moves by Prime Minister Narendra Modi: a late 2016 ban on then circulating high-value currency notes, and the nationwide introduction of a goods and services tax (GST) in 2017, reports Reuters. Some economists opine that Modi’s two signature political gambits: demonetisation and GST contradicted the intentions and turned out to be devastating to the Indian economy.

We ought to acknowledge the alarming situation and act against it. “A $55 billion funding market is drying up and threatening a chain reaction. The next prime minister must fix it, and quickly,” says Andy Mukherjee, Bloomberg.

Also Read: 38% Of The Companies Used In India’s GDP Calculations ‘Not Found’ Or ‘Surveyed’: NSSO Study