A Reality Check Of Menstruation In Rural India

2 May 2017 12:29 PM GMT

Much has been assumed regarding the sanitary pad usage in rural india. The general perception is that, sanitary napkins are not available or affordable by rural women and girls. It will therefore come as a surprise to many that, even in the rural areas, the prevalence of disposable products for managing menstruation is much higher than the 12% number often quoted. The study was conducted by A.C.Neilsen and endorsed by Plan India in October 2010, which stated that only 12% Indian women use Sanitary Napkins and the rest are using unsanitary methods of managing menstruation. However, this study titled “Sanitary Protection: Every Woman’s Health Right” is not available on any public domain.

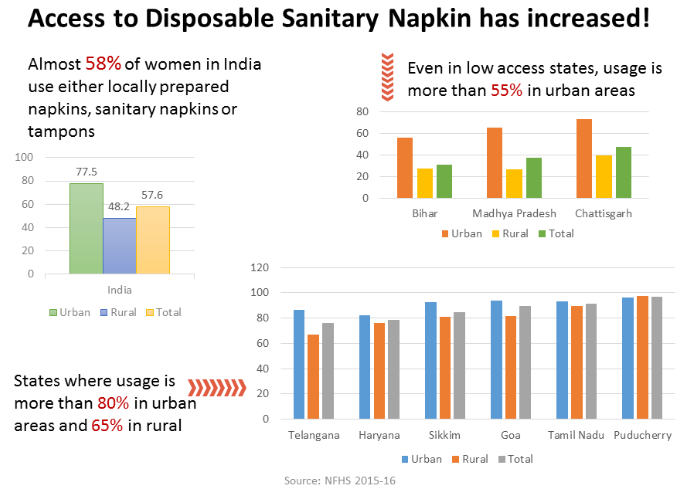

This was a 2010 study. Years later, most CSR programs, NGO interventions and even Government schemes are still based on this “12%”. What’s more, it is assumed that the rest 88%, that do not use sanitary napkins, must be using unsanitary means. According to National Family Health Survey, NFHS 2015-16, the numbers both in rural and urban India are far higher than this.

The NFHS 2015-16 survey pegs the number for women using hygienic means of managing menstruation in India at 78% in urban areas, 48% in rural areas and 58% overall. Today, nearly 6 out of 10 women in India have access to disposable sanitary napkins. According to this survey, locally prepared napkins, sanitary napkins and tampons are considered as hygienic methods of protection. One can assume from the language used that single use disposables are considered hygienic. There are wide variations in usage of ‘hygienic products’ across different states, with Tamilnadu, Kerala and Delhi as high as 90% and rural Bihar as low as 30%.

Pass the pad please

Government has been running free sanitary pad programmes in rural areas where a girl student receives a pack of pads on a regular basis. Scheme for promotion of menstrual hygiene has rolled out in 17 states in 1092 blocks through Central supply of ‘Freedays’ sanitary napkins. Till August 2014, over 1.4 crore adolescent girls have been reached and 4.82 crore packs of ‘Freedays’. (Courtesy: mohfw )

However, recently published article in a leading daily, The Hindu shows that such government programmes are often marred by lack of funds, as ensuring a continuous supply of disposable single use pads is not a one time expense. Not only are such programmes financially unsustainable for governments, but are also inadequate as girls receive only about 5 or 6 pads per month. There also exists a large gap between the guidelines and the actual practices in these schemes in terms of execution and quality of pads distributed. A detailed report on one such scheme in Kerala touches upon these issues.

The quality of pads handed out in most programs is sub-standard, says Kavya Menon, a Bio-Technology graduate from IIT Madras who has first hand experience of reaching out to nearly 700 girls in 15 villages while working in Vedaranyam, a rural municipality in Nagapattinam district. To manage a normal period, 12-20 pads are required on average. Anything less than that means changing less often and leading to reduced hygiene. 5 pads is not sufficient anyway!

Government. NGO and CSR programs that distribute sanitary napkins are based on the assumption that adolescent girls drop out of school because of lack of sanitary products. Interestingly, there is no substantive research or data to back this assumption – that providing sanitary napkins free or subsidized to school going girls increased their attendance or performance. In the absence of supporting data, what is so simplistically reduced to access or lack of products, is actually a more complex situation. Shradha Shreejaya, a menstrual hygiene advocate and educator at Sustainable Menstruation Kerala collective, who has worked in Assam, Odisha, Tamil Nadu and Kerala at various times, opines that the girls miss school during periods due to two main reasons – Period cramps and lack of private changing space and clean toilets. Ground situation is not very different in Rajasthan.

Can crores of rupees pumped into schemes such as these providing free disposable pads to girls be put to better use by maintaining existing toilets with clean water access instead?

Is cloth unhygienic?

Our underwear is made of cloth and that is not unhygienic, so why should cloth for menstruation be considered unhygienic? Perhaps, we as a culture, directly associate cloth with lack of hygiene because of the way we view menstruation!

That said, due to such a culture and unreasonable taboos, most women end up being denied access to clean cloth (and sunlight!) and dry their menstrual cloth in damp nooks and corner areas or under other clothes, as a result it makes them highly susceptible to infections. The journal on a study in Orissa conducted in 2015 [4] establishes a direct correlation between urogenital infection and bacterial vaginosis with users of reusable pads compared to users of disposable pads. However, it also clarifies that hygiene management practices, access to clean water and private changing areas for women were not explored in this study. Possibly more such studies need to be conducted to explore this aspect to ensure that women follow hygienic practices in storing and washing their reusables.

As to the correlation between reproductive tract disorders and use of cloth, Sinu Joseph, who undertook an intervention called Menstrual Health of Karnataka, covering 1058 adolescent girls and women across 4 districts in Karnataka in association with NRHM last year, debunks that theory. She quotes in her study, supported by compelling data mythrispeaks that prevalence of menstrual disorders is higher in developed countries than in developing countries. Also, according to the study, absenteeism in schools during menstrual days is not a result of lack of menstrual products and toilets.

Quoting from the study – “A comparison of data owing to school absenteeism during menstruation in developing nations shows that the percentage of girls who remain absent during menstruation is around 12.1% in China, 15.6% to 24.2% in Nigeria, 24% in India and 31% in Brazil. If the current hypothesis – that school absenteeism is due to lack of toilets or Sanitary Napkins – is true, then surely developed countries must have little or no absenteeism. However, data indicates that it is no different in developed countries. Studies indicate that 17% teenagers in Canada, 21% in Washington D.C, 24% in Singapore, 26% in Australia and 38% in Texas miss school owing to menstruation.”

Perhaps those skipping school during period days prefer the comfort of home or may have severe cramping or excessive bleeding. But the study suggests that lack of products or toilets cannot be the cause, at least in developed countries. Quoting from another PLOS study – “Although there was good evidence that educational interventions can improve MHM practices and reduce social restrictions there was no quantitative evidence that improvements in management methods reduce school absenteeism.”

The practice of rituals and taboos associated with menstruation could also be the reasons why girls missed school during period days as claimed in the report put together by Auroville Village Action Group (AVAG).

Lack of water in villages?

With anecdotal evidence gathered from many cloth pad users, most say that one needs 5-8 cloth pads per period to allow for drying and flow. Amount of water required to wash a cloth pad, hold your breath, is not significantly different from that required to wash underwear or clothing of similar size. Roughly, 3-4 mugs of water is needed to soak, soap-wash and rinse a cloth pad.

Laura O’Connell from Ecofemme, a cloth pad marketing group based out of Auroville, opines: “We believe that most regions in rural India do have the resources to continue their traditional practice of using washable cloth for menstruation.”

Most NGOs and educators working in rural India agree that menstrual cups are excellent solution for married women in rural areas with water shortage. But the idea of promoting menstrual cup in India has mixed takers mainly due to the cultural aspect and vague notions of virginity. Use of an internal device such as menstrual cup also requires more hand-holding for the user in terms of usage, maintenance and troubleshooting, without which the transition may not be successful. Interestingly, in the past, women did insert cloth like tampons to absorb menstrual flow, but we have not looked for documented research on this topic yet.

In rural scenarios, the choice to promote menstrual cup varies depending on the educator and most take into account the cultural sensitivities around this topic. There have been instances of rural women embracing the menstrual cup. A behavioral experiment [6] on 960 rural women from 60 villages in rural Bihar quotes reasonable success (30%) with introducing menstrual cup.

Why are rural women moving to disposable pads?

The report put together by Auroville Village Action Group, January 2011 (AVAG) [7] deals with various aspects of menstruation hygiene management and attitudes towards menstruation, exploring socio-economic factors. Their findings suggest that costs, familiarity of habit and to some extent, comfort are the biggest motivators for women to choose cloth over disposable pads. It also indicates that concerns for environmental impact of disposable pads are not a motivating factor for women to stay with cloth. Around three-fourth of cloth-users in the AVAG study had concerns about changing the cloth when not at home. The mentioned obstacles included lack of private space or feeling too ashamed to either wash, dry or dispose the cloth in public.

Use and throw convenience of disposable sanitary napkins, the aspirational aspect projected by the popular media and the inconvenience in maintaining cloth given the social taboos surrounding the menstrual cloth seem to be major reasons for the rural women migrating to disposables.

Sanitary waste – Making a mountain out of molehill?

Most groups and NGOs who work in the area of menstrual hygiene awareness report rising use of sanitary napkins among the rural women for various women. However, in rural areas there is no collection or transportation of waste. Most women end up disposing their used pads with other waste. Some of them burn it or dispose it in the latrine. Some users wash the blood out before disposing the pad with other waste. Mostly they end up going distances to burn or bury since taboo requires them to not dispose off these things near temples or agriculture land to prevent “polluting” them.

Quoting from a recent article in Quartz India, regarding the MHM situation in a village in Jharkhand. https://qz.com/910094/sanitary-napkins- form-the- bed-of- a-bathing- pond-in- india-what-personal-hygiene- is-like- for-rural- women/

It was also observed that majority (73%) of the women use cloth during periods. Most of the women, around 72%, clean the cloth where they take bath. It was unfortunate to acquire the information that they wash their used cloth during the menstrual cycle in the same source where they were taking bath.

Only 3.4% reported disposing the napkin safely with other wastes, while 17% said they dumped it in the same pond. “We place the soiled napkin in between the fingers of our legs, and while we dip inside the water to take bath, we release it then and it sinks down to the ground,” a 13-year-old girl said. “If you search the bottom of the lake, you will find the whole bed covered with napkins,” said the mother of a 15-year-old who uses sanitary napkins.

Taboos affecting MHM in rural India

Attitudes are surely changing with times. But we have a long way to go when dealing with menstruation and women’s needs. Even today, there are communities who believe menstruation is a curse to girls and a health problem. Making products available is not doing much to this seldom talked about topic that affects 50% of the population. Good menstrual hygiene practices needs to be talked about and discussed in the open for the sake of economic and environmental sustainability and health. There is need to involve men in menstruation. Many issues related to functioning toilets, access to safe private spaces and clean water need to be sorted, often times at the household level, to give the rural women a decent shot at having a healthy reproductive life and beyond.

Lastly, in search of a readymade solution that fits all immediately, lets not trade one evil for another. Lack of good menstrual hygiene practices and the silence surrounding menstruation cannot be replaced by a non-biodegradable disposable product with unnaturally long life cycle. Eventually, what goes around, comes around!

References

- NRHM, Review of Performance, http://www.mohfw.nic.in/WriteReadData/l892s/8589632147856985.pdf

- Article in The Hindu dated March 27th, 2017, The failure of Suchi schemes.

- Report on Rapid Assessment of the Scheme for Promotion of Menstrual Hygiene in Kerala, 2013, SreeChitraTirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology, Trivandrum, Kerala

- Menstrual Hygiene practices, WASH Access and Risk of Urogenital mutilation in Women from Odisha, India, 2013, Public Library of Science.

- A Systematic Review of the Health and Social Effects of Menstrual Hygiene Management, 2013, Public Library of Science.

- Learning by doing something else: Experience with Alternatives and adoption of a high Barrier menstrual Hygiene technology, 2014. Hoffman, V., Adelman, S,, and Sebastian, A..

- Report on Menstrual Hygiene Management in Villipuram District, Tamil Nadu, Jan 2011, by Auroville Village Action Group.

About the author – Shilpi Sahu is a Multimedia Engineer by the day, self proclaimed artist by night and amateur long distance runner by dawn, who is passionate about sustainable living and preservation of urban commons.

This is the second article in the series of seven for Earth Day and is done in a collaboration with Bhoomi College, a center for learning for those who wish to take up green paths, as well as those who wish to live with more ecological consciousness and personal fulfilment. The last article in the series of seven will be published on Menstrual Hygiene Day On 28th May.

In these 7 weeks, we will cover a variety of topics around menstruation, which are eye opening, thought provoking and will inform you more about sustainable menstruation options. We urge our readers to stay tuned and participate in this crusade.

Also read: Period Shaming – What We Ought To Do

All section

All section