Source: Catch News | Author: Anna Verghese

If something has collectively consumed our imagination over the past few days, it’s Lance Naik’s Hanumanathappa’s almost unbelievable resilience before his body finally gave in to the assault of nature.

But while the conditions in Siachen – and what soldiers like Lance Naik Hanumanathappa went through – may be incredible to us, the heroes who sign up for this take the risk to their lives entirely in their stride.

Evidence of that is Sachin Bali, a young ex-army man in his late 30s who less than 15 years ago was out there in the same brutal ice fields of Siachen.

And two-and-a-half years into his army life, he led a post-avalanche rescue mission much like this one – one that resulted in him losing some of his fingers and toes to frostbite.

And yet talking to Bali, one begins to grasp a reality beyond jingoistic nationalistic slogans: that when they sign up to serve the country, these young boys and girls make their peace with death in a way no civilian can understand. Life becomes just one more tool at their disposal to protect their borders.

Had you always planed to join the army?

In my final year at college, when it came down to deciding the future, this was one thing I felt I could relate to. I couldn’t think of anything else that suited my temperament – I’d read the news, I’d see the army lifestyle, the action they’re engaged in, and it was something I could relate to. My parents wanted me to do an MBA, but I said no.

I wanted to give five years to the army and see how it went. To be physically present and contribute to the country, as rhetorical as that sounds.

What triggered it?

You keep reading the news and seeing that these soldiers do, the lifestyle they follow, the action they’re engaged in, and it was something I could relate to.

What about your parents?

I didn’t tell them I was applying for the forces – it was only later when I got the warrant from the army for an interview that I did. They were surprised, but I’ve had their support.

And you were how old?

21 at that time, 22 when I got commissioned.

And your first posting?

The infantry unit I had been placed with was selected to go on a UN mission for a year, so I went to Ethiopia and Eritrea. I wasn’t happy about it because this wasn’t what I had signed up for. I’d rather be here and fighting for my own country instead of someone else’s war.

Why did that matter? It’s still humankind you’re fighting to defend!

True, but my core motivation at the time was my country. I was a bit selfish that way. And there was so much happening in India at the time. This was just after Kargil, so I was eager to be here.

And then there’s the fact that these UN stints are thought to be cushy postings. I didn’t want to be stigmatised as someone who went for this as my first posting.

What was the actual experience like?

It was incredible. We went there six months after the war had ended, but the effects of war were everywhere. There were bodies lying around, unexploded ordinances, broken tanks etc. Our job was to clear the area and to go to the camps and bring home the people who had been displaced. In that sense it was a very fulfilling job, you’re helping people piece their lives together after a war. And then for me personally, it was also where I caught my travel bug, a desire to experience other worlds, other cultures.

And on your return to India you were selected to go to Siachen? How did you feel about that?

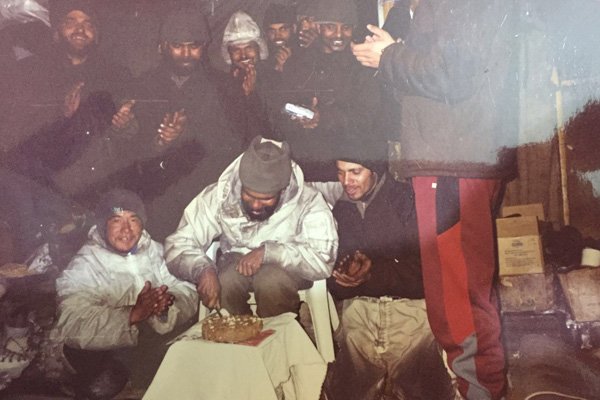

Yes, from Nov 2002, and my stint ended, in an unforeseen way, in March 2003. I went through advanced training to handle that terrain and to lead a team there and was placed at one of the forward posts. There are a number of factors involved in a Siachen placement, from the need to be in peak physical shape, as well as mental attributes. It’s a matter of prestige to be picked for that posting – you aspire to it.

Tell us the incident that cost you your toes and fingers – and eventually your army career.

So, March is when the snow starts to melt and it’s a risky time in the glaciers because of rockslides and avalanches. This particular incident was on March 2, 2003. I had ten posts under my command and every day I needed to do an OK-report with each of them.

It had been snowing for a full week and there were blizzards. Temperatures were at -45 and -50 degrees C. While I was doing my regular check-ins with one of the posts, called Mangesh, the line went dead.

I knew immediately that something was wrong; I thought there might have been an avalanche. I tried to reach the post repeatedly but couldn’t. I then contacted the battalion HQ and told them my fears. They conducted sorties the next morning to try and figure out what had happened. As we feared, there had been an avalanche. Six of the men could not be located. Six more were out in the open with minimal clothing. Some didn’t even have shoes on. Chopper sorties were trying to drop clothing but they kept sinking in the soft snow. A helicopter cannot hover at one point at such an altitude due to the air being thin. We knew we had to get them out before night if there was any hope of them surviving.

That was when you decided to organise a rescue mission?

Yeah, I got a team together and we organised ourselves and set out on the mission. It’s a complex task, let me give you a brief overview. You move in two groups. The first is the route opening party, in this case that was me and three other guys. We were headed to half-link first – half-link is the midway camp between that post (Mangesh) and ours. We maintain a distance of 100 metres between the two groups in case an avalanche happens, so both teams won’t be at risk and can rescue each other if needed.

Walking in waist-high soft snow is extremely tough. You take three steps and get tired – and this is men in peak physical condition. Your body is functioning with 30% of the oxygen it needs. So the first person takes three steps, then the one behind takes the lead. And we keep going like that to ensure no one tires out. If you sweat even a bit extra, that sweat becomes ice if you stop walking. So it’s a fine line and you need to scientifically work through it.

How far was your forward post to half-link?

Not more than 500 metres. On a normal day it would have taken us 20 minutes to get there. That day it took almost two and a half hours. And you need to keep following the route markers because there are crevices all around – which are invisible under snow. Except the markers too were invisible on that day. We finally reached half-link, took a 15 minute break and continued to Mangesh. Usually that journey would take us no more than an hour. On that day, we took ten gruelling hours instead because we couldn’t see anything in front of us.

Can you describe the extent of cold in some way?

Mid-way to Mangesh, our hands and feet were frozen – this despite the best equipment possible. Our jaws were locked because of the cold. At such temperatures you’re simply not allowed to be outside for more than two hours at a stretch, irrespective of what you’re wearing. You need to come back, put your hands and feet in lukewarm water and salt and get your movement back.

But at that point our aim was to get these men back to safety. Sadly we hit a mound of soft ice and there was no way we could move past that point. We continued to search for a while and finally took a collective call to return to half-link. We communicated with HQ and fortunately, the men at Mangesh were eventually rescued.

Your team by then had been out in the cold for about 2 days? What did that do to you all?

Some of my men were starting to speak incoherently and were a bit lost. I myself got an eerie feeling, of being in a super-calm place. I could hear a buzz in my head. I felt as if I was in a really comfortable space, and I should set up camp here and make a cup of tea and everything would be alright. Then my training kicked in and I realised my mind was playing games – that was the signal that something was very wrong and we needed to turn back. My biggest fear was if one of us was injured and needed to be carried back – that would have been impossible.

When we reached half-link, they gave us something to drink but it burned my throat – I thought it was too hot but realised the insides of my throat were injured from exposure to the icy air. I couldn’t eat or drink.

The helicopters came the next day and after a lot of difficulty we managed to evacuate our team. At the hospital, they couldn’t recognise my face because it was swollen from the cold.

Either way the damage was done. You cannot reverse the effects of frostbite so I ended up losing some of my fingers and toes.

How did you reconcile to that?

It was fine.

Really? Surely it changed your life in some way.

Sure, in some ways. But then you learn to move on. There’s no point dwelling on that.

Is the loss of life worth having this presence at Siachen?

What other choice do we have? Give the area up to Pakistan? History has evidence to prove that we can’t trust them by de-militarising the place.

The media has called the soldiers that died at Siachen recently martyrs. Is that your opinion?

I don’t have an opinion on semantics. They were proud to do their duty. Unfortunately they had to pay the price for serving where life took them.

What is it that drives these men, and men like you, to put yourselves in such bitterly hostile situations?

See, most of the men in areas with glaciers are volunteers. It might sound foolish but it is a matter of pride to be at places that are the harshest and most challenging. This is how we see us grooming our army for possible war. So people want to do it. That’s a good thing. Nobody shies away.

The army offered you a desk job post this incident which you turned down!

Yes, because I’m a battle casualty the army said they would take care of me. But I didn’t see myself at a desk job. It wasn’t what I signed up for. I decided I’d rather do something else.

How did you deal with having to leave the army?

I got through it. It’s natural for me, for my temperament, to move forward, so I did.

So you didn’t feel like it was a big loss?

Hardly. Maybe for like 30 seconds, when I saw the actual extent of the injuries. But I told myself that this is me, and I kept myself happy.

Is that because of the person you are or because the army trained you to expect this, given the risks involved?

I think both. Strong family support and upbringing go a long way. And inherently I am a happy person. At the same time I knew this is what I had signed up for. In fact it sounds odd, but I actually had a feeling that something would go wrong at the time I joined the army. But it was my decision and I live with the consequences with no regrets.

How different was moving into civilian life?

The army is a 24/7 job – for instance Siachen, which is face-to face-with the neighbour, means you need to keep round the clock vigil and alertness. The location and weather demand it. There is round-the-clock duty, a day never really ends. However a day would include sentry duties, training, break and sleep time. Post one’s duty hours, one is involved in practicing drills, including glacier survival and rescue drills, weapons training, general information classes, area maintenance, kitchen duties and rest time. One may stay awake during the night and go to sleep during the day depending on one’s duty shift.

Now, though, I have so much time for myself! I work five days a week and can do other things too.

When you’re out there in the frozen cold, do you think of what awaits you at home?

I was single at that time, so if something were to go wrong, there was no ‘baggage’. I had let go of a few things before I joined because I had a hunch. Parents are a given, you can’t let go of that.

How do soldiers at this type of post deal with the possibility that you may never see the people you love again?

It doesn’t cross your mind.

Why?

I think it’s only when something bad happens that you think of them. But on a daily basis these attitudes and thoughts don’t arise. You do the job you signed up for.

Out there in Siachen, how do you cope with the isolation?

There is a roster and you take turns being on guard duty, cooking, cleaning, studying, rescue drills, maintaining the guns, etc. We have books and in some places dish antenna. So you have a routine. Otherwise your mind starts playing games. In that extreme a terrain, you can’t afford to be distracted by thoughts of home or of outside concerns. I was required to constantly know what was going on with my men. If a guy suddenly became quiet or was behaving indifferently, you needed to look into it.

That kind of snow can mess with you internally. We’ve had men who looked perfectly fine. Five minutes later they were dead.

Is there a sense of fatalism you need in order to join the army?

No. You don’t go into it thinking that something bad will happen. Rather, you know that this is the work you want to do. From my point of view, that fatalism is not there.

So you’d still say it’s just another job?

Absolutely. It’s part of what you signed up for. Don’t come to the army if you have second thoughts.

Read More At: Catch News