Image Source: sigmalive

Background:

In 1950, the population of China exceeded 500 million, but a proposal to pass a law on contraception and abortion in 1953 was put into cold storage due to political upheaval and the famine of 1959-61. Left unchecked, China’s population crossed 800 million by 1970. Since the fertility rate stood at 5.5, China implemented a policy which encouraged people to marry later and wait longer between children. There was a slogan, “Later, Longer and Fewer” which was adopted by the State in 1975 and which urged urban couples to have no more than 2 children and rural ones to limit it to three. By 1979, China’s fertility rate had dropped to 2.7 and in 1979, it implemented the one-child policy. It was supposed to be a one-generation policy.

Exceptions to the Rule:

There was a change in the policy in 1984 which allowed a second child for many families in rural areas, especially if the first was a girl, or a disabled child. Some ethnic minorities were allowed an extra offspring and this led to many people dubbing the policy as a “one-and-a-half child” policy. In 2001 new laws allowed local governments to impose fines (“social child raising fees”) for additional children.

There was another exception allowed in 2013 which allowed two children if one parent came from a household without other siblings. A birth spacing (3-4 years) was enforced in case of the second child. If a child was born in overseas countries, they were not counted if they did not obtain a Chinese citizenship. Also, Chinese citizens returning from abroad could have a second child. If the first child died due to a natural calamity like earthquake, the couple was allowed to have a second child. Effectively, in 2007, only 35.9% of the Chinese were actually subject to the one-child policy.

Implications of China’s One Child Policy

A conservative estimate by Beijing states that the government collects around $3 billion a year in related fees. On the other hand, 23 of China’s 31 provinces collected $3.1 billion in fines in 2013, according to an independent analysis by a Chinese lawyer. This meant that wealthy families which could afford to pay the fines were exempted from the rule. They generally went for second or even a third child. China’s migrants were also reasonably sure that they could avoid fines altogether and violated the one-child policy.

Moreover, the one-child policy led to gross violation of human rights, like forced sterilization, forced abortions, sex-selective abortions or infanticide targeting girls because of the social preference for male child. In 2012, a shocking incident of a woman who was seven months pregnant was abducted by family planning officials in Shaanxi province and forced to have an abortion came to light. Many girls are forcibly given off for adoption immediately after their birth.

This has led to a skewed sex ratio in the country. The sex ratio at birth (between male and female births) in mainland China reached 117:100 and remained steady between 2000 and 2013, substantially higher than the natural baseline, which ranges between 103:100 and 107:100. According to Steve Tsang, a professor of contemporary Chinese studies at the University of Nottingham, “We are talking about between 20 million and 30 million young men who are not going to be able to find a wife. That creates social problems and that creates a huge number of people who are frustrated.” Quoting examples from history, he opines that countries with a very high number of unmarried men of military age were “more likely to pursue aggressive, militarist foreign policy initiatives”.

The one-child policy led to birth tourism which meant Chinese women gave birth to their second child overseas. Hong Kong was a favourite but now it has reduced the quota of births set for non-local women in public hospital, leading to dramatic surge in the fee for delivery of babies.

Many children born outside the one child policy were not registered at all and were called “Heihaizi” or “black children”. Since they were not able to get a birth certificate, they did not legally exist and were outside the coverage of most public services, like education and health, and protection under the law.

Then there are potential social problems since some parents over indulge the only child. Such children are called “little emperors” by the local media. There was an apprehension that it may lead to poor communication and cooperation skills amongst the children with no siblings. According to one statement by some 30 delegated to the Chinese government in 2007, “It is not healthy for children to play only with their parents and be spoiled by them: it is not right to limit the number to two children per family, either.”

There are real psychological and economic costs to be paid by parents who have lost their only child in China. The term for such parents in China is “Shidu” and they are not allowed entry in many nursing homes because they do not have any progeny to authorize treatment or act as guarantors. They even find it difficult to obtain plots of land for their own burial or that of their child since there would be nobody to pay for the maintenance charges of the plots. There are one million Shidu parents in China. They need to be taken care of by state authorities.

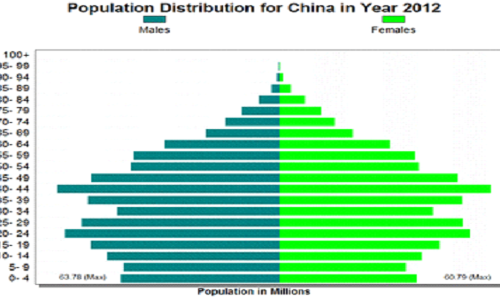

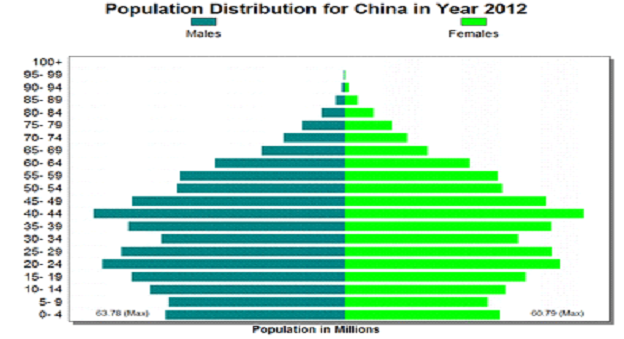

This brings us to the immediate concern which led the Chinese authorities to abolish the one-child policy. Although the old policy prevented over 400 million births in the country, now China is sitting on a “demographic time-bomb” as its 1.3 billion population is ageing rapidly and the country’s labour pool is shrinking. The population pyramid of China, according to International Futures, is as given below:

The number of people aged 60 or above reached 212 million at the end of 2014 (15.5% of China’s population) while the number of disabled elderly approached 40 million.

According to a UN estimate by 2030, people above the age of 65 will account for 18% of the country’s population and by 2050 China will have about 500 million people over 60 which is more than the population of the USA. Meanwhile, the working-age population (between 15 and 59 years) fell by 3.71 million last year (2014) a trend likely to continue. There is going to be an acute labour shortage.

Chinese people will spend over USD 1.54 trillion from 2016 to 2020 on elderly care, increasing 17% per year, according to a report published by Price Waterhouse Coopers earlier this month.

Abolition of the One Child policy:

In the wake of these concerns, the Chinese lawmakers passed the historic decision allowing all couples to have two children from 1st January, 2016. The new law was ratified on 27th December, 2015. China will “fully implement a policy of allowing each couple to have two children as an active response to an ageing population”, the party said in a statement published by Xinhua, the official news agency. “The change of policy is intended to balance population development and address the challenge of an ageing population.”

Response from Various Quarters:

The abolition of this policy has evoked mixed response from different stakeholders. Those who had been demanding a change in policy have welcomed the move as something positive. For example, Ting Lu of Bank of America believes that this reform might lead to around 9.5 million incremental babies being born.

However, experts believe that a shift to a two-child policy might have come too late and might be too little to now contain the looming population crisis. It would prove difficult to dismantle enforcement mechanisms for population control due to deeply entrenched bureaucratic interests. After all, the fines on more than one child prove to be highly lucrative to the state exchequer.

Human rights activist believe that there is only a change in policy (two child policy) which means the Communist Party continues to control the size of Chinese families. Willaim Nee, a Hong Kong-based activist for Amnesty International states, “The state has no business regulating how many children people have” and any law which limits the number of children should be abolished. After all, at the end of the day, it is about a woman’s reproductive rights.

There could still be sex selective abortions or forced abortions.

Moreover, in urban areas many couples are reluctant to have two children due to high cost of living and raising a child. This means the relaxation of family planning rules may not have a lasting demographic impact. Many women do not want to compromise on their careers by raising more than one kid.

There is a question mark on single parents outside wedlock which will continue to be penalized.

Some experts opine that the fines that were imposed on more than one child could be utilized to launch more social service schemes for the elderly affected over the years. Since the decision to abolish the one child policy is related to the country’s demography it is going to take time to actually show the result. After all, babies have a natural gestation period. The ageing population of China needs to be taken care of in the meantime.

While The Logical Indian community hails the latest easing of China’s one-child policy, we hope that various stakeholders like Shidu parents, the elderly, especially the disabled ones, the women on whom the responsibility of raring a child falls, and those concerned with human rights violations, are satisfactorily addressed.