“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” – Martin Luther King Jr.

If justice is blind, why does it so often recognize wealth?

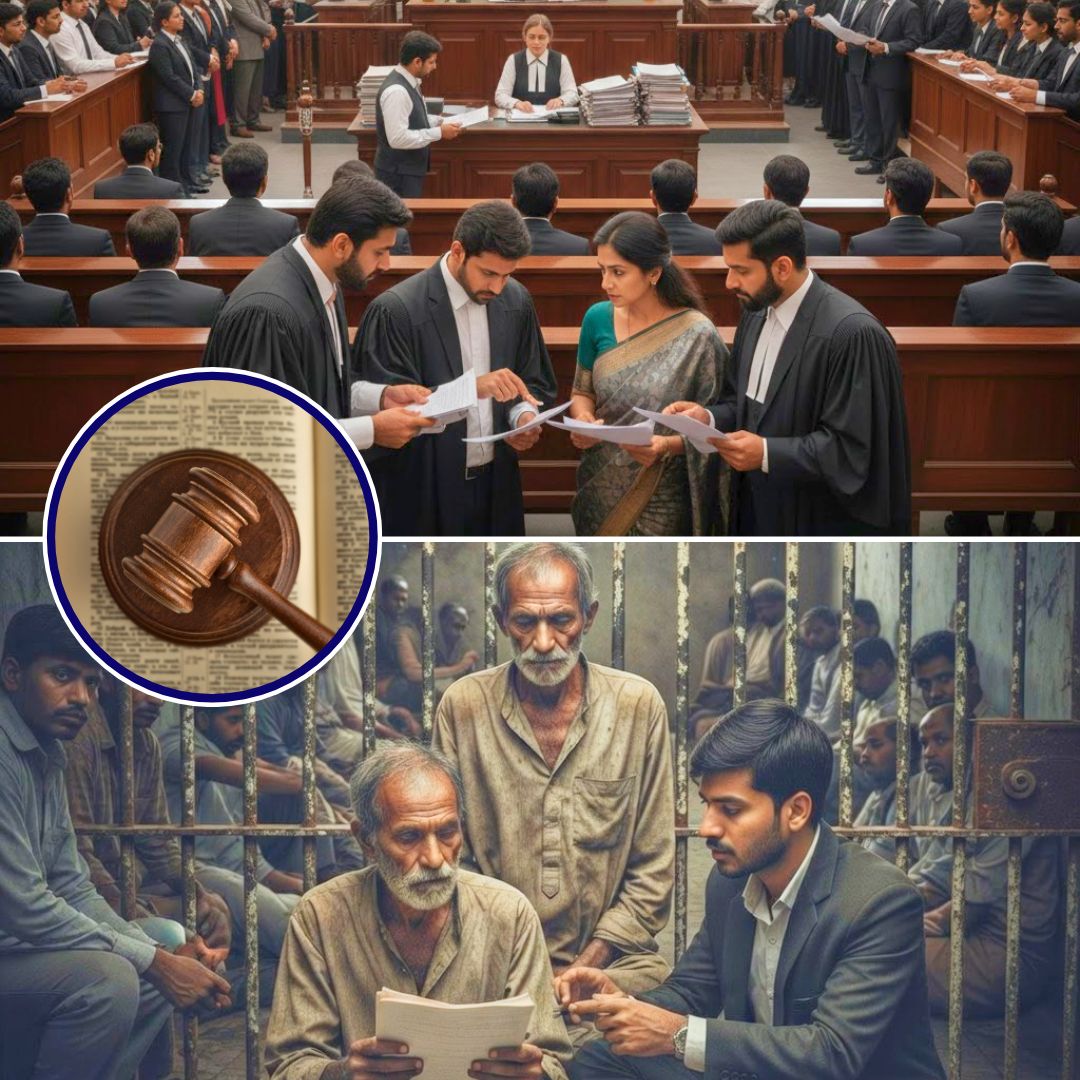

In courtrooms across India, two parallel realities unfold. In one, high-profile accused secure swift bail, seasoned legal teams, and procedural relief within hours. In the other, nameless undertrials – often poor, often forgotten – wait years behind bars for trials that crawl through an overburdened system. The Constitution promises equality before law. The lived experience suggests otherwise.

A Tale of Two Indias in the Same Courtroom

Recently, in Uttar Pradesh, the son of a wealthy businessman involved in a high-profile luxury car crash was granted bail within hours of arrest on a modest personal bond. The speed of the process triggered public debate – not merely about one individual case, but about a pattern many Indians instinctively recognize.

Contrast this with the data from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB):

- Over 75% of India’s prison population consists of undertrials – individuals not yet convicted.

- Tens of thousands have spent over one to three years in prison awaiting trial.

- Many are incarcerated for minor, bailable offences.

The question becomes unavoidable: if liberty is the norm and jail the exception, why does poverty reverse this principle?

India’s Global Standing: What the Numbers Say

According to the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index 2024, India ranks:

- 79th out of 142 countries overall

- 89th in Criminal Justice

- 111th in Civil Justice

The Civil Justice score is particularly revealing. It measures whether justice is affordable, free from discrimination, and delivered without unreasonable delay. Ranking 111th signals systemic barriers for ordinary citizens seeking fair redress.

Domestically, the India Justice Report highlights:

- India has around 21,000 judges for a population of over 1.4 billion.

- That translates to roughly 15 judges per million people, far below the Law Commission’s recommended 50 per million.

- Crores of cases remain pending across courts, many stretching beyond five years.

Justice delayed is not merely administrative inefficiency – it is structural inequality.

When Wealth Buys Time – and Time Is Justice

Legal battles are expensive. Top-tier lawyers charge fees inaccessible to most Indians. Filing repeated applications, appeals, and procedural challenges requires resources. Even securing bail can depend on arranging sureties or bonds that poorer families struggle to furnish.

As Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer once observed:

“Bail is the rule and jail the exception.”

Yet, in practice, jail often becomes the default for the economically vulnerable.

Wealth doesn’t necessarily guarantee acquittal. But it frequently guarantees speed, strategy, and stamina — three factors that heavily influence outcomes. Poverty, by contrast, often guarantees delay.

A Global Comparison: What Equal Justice Looks Like

Countries like Denmark, Norway, and Finland consistently rank at the top of rule-of-law indices. Their systems share common features:

- Higher judge-to-population ratios

- Strong, state-funded legal aid

- Strict timelines for trial progression

- Transparent bail standards

In these nations, access to justice is not determined by bank balance.

India, by contrast, struggles with vacancies, infrastructure gaps, and uneven legal aid quality – conditions that amplify socioeconomic disparities.

The Constitutional Promise vs. The Courtroom Reality

The Constitution of India enshrines equality before law under Article 14. But constitutional morality must translate into courtroom practice.

When undertrials lose years of their lives before acquittal, the eventual “not guilty” verdict cannot restore lost livelihoods, reputations, or dignity. The punishment, in effect, precedes the trial.

This is not merely a legal flaw. It is a democratic contradiction.

The Way Forward: Making Justice Truly Affordable

If India is to bridge the gulf between promise and practice, reforms must be structural:

- Expand Judicial Capacity – Fill vacancies urgently and increase judge strength toward recommended benchmarks.

- Strengthen Legal Aid Systems – Ensure quality representation, not symbolic appointment.

- Bail Reform and Undertrial Review – Automatic, periodic review of long-pending undertrial cases.

- Digital and Procedural Efficiency – Reduce adjournments and procedural delays.

Justice must not be indexed to income.

A Closing Thought

A democracy is not judged by how it treats the powerful – they will always find representation. It is judged by how it treats the powerless.

If freedom can be secured within hours for some, but denied for years to others, then justice is not blind – it is selectively sighted.

And a nation that allows wealth to determine the speed of justice risks turning its courts into corridors of inequality.

The real test before India is simple:

Will justice remain a constitutional guarantee – or continue as a purchasable privilege?

The Logical Take

At The Logical Indian, we believe justice must be equal in access, not just in principle. Bail should not depend on wealth, speed should not depend on status, and liberty should not depend on influence.

A fair legal system protects the vulnerable first. Until justice moves at the same pace for rich and poor alike, equality before law remains a promise unfulfilled.