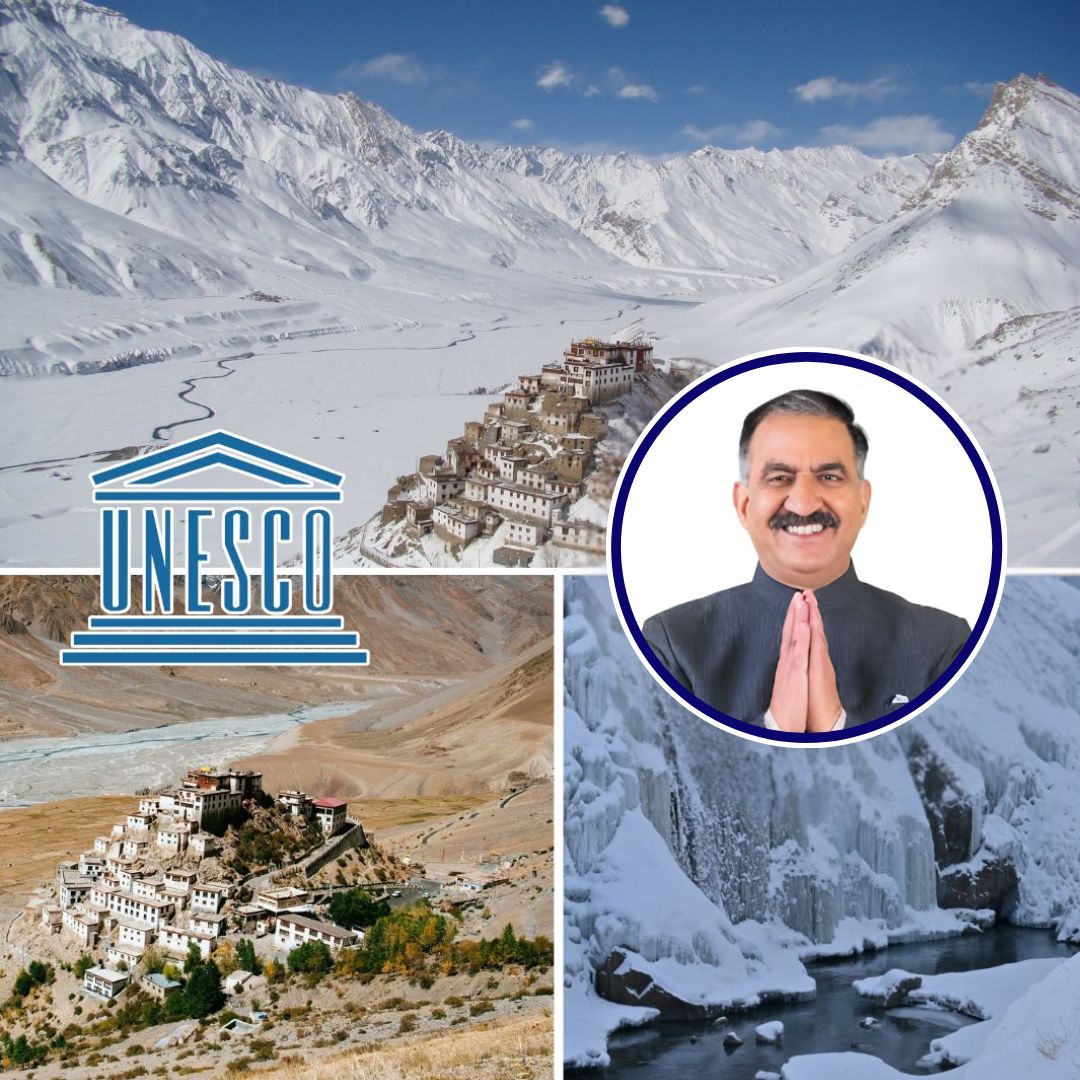

In a landmark decision, UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme has officially recognised Himachal Pradesh’s Spiti Valley as India’s first Cold Desert Biosphere Reserve. Announced during the 37th session of the MAB-ICC in Hangzhou, China, in September 2025, this designation places the rugged, high-altitude landscape into a global framework for ecological conservation.

Covering 7,770 square kilometres in the Lahaul-Spiti district, the reserve includes some of the Himalayas’ most fragile ecosystems, unique biodiversity, and traditional communities living in extreme conditions.

The move marks a significant step forward in India’s conservation efforts, now including 13 UNESCO biosphere reserves, with Spiti being the first high-altitude cold desert habitat recognised on this scale.

Significance and Geographical Scope

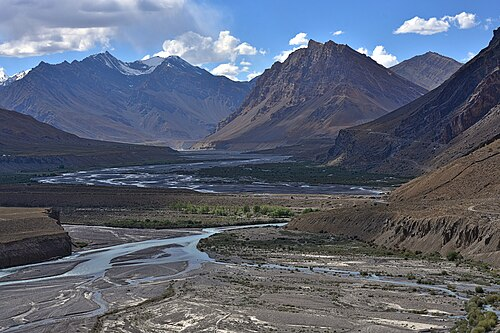

Spiti Valley, situated at altitudes between 3,300 and 6,600 metres, represents one of the coldest and driest ecosystems globally. The reserve encompasses multiple protected areas, including Pin Valley National Park and Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary, and extends into the

Chandratal Wetland and Sarchu Plains. Structurally divided into core, buffer, and transition zones, the reserve aims to balance ecological preservation with sustainable human activities. The core zone covers 2,665 sq km, strictly protected for wildlife like snow leopards, Tibetan wolves, and Himalayan ibex, alongside over 800 blue sheep that form a vital prey base for predators.

Himachal Pradesh’s Chief Minister Thakur Sukhvinder Singh Sukhu lauded the recognition, emphasising the government’s commitment to protecting natural and cultural heritage amidst climate change challenges.

Ecological and Cultural Significance

Despite harsh environmental conditions, Spiti’s ecosystems sustain a remarkable diversity of flora and fauna. The region is home to 655 herbs, 41 shrubs, and 17 tree species, including endemic and medicinal plants vital to traditional healers practising Sowa Rigpa or Amchi medicine.

The wildlife population includes 17 mammal species and 119 bird species, with snow leopards as its flagship species. Other critical animals are the Himalayan wolf, Tibetan antelope, and Himalayan griffon vulture, underscoring the region’s ecological richness.

Human communities in the area have adapted over centuries, practising pastoralism, yak herding, and farming, often using traditional herbal knowledge. Recognising the biosphere’s global importance is expected to promote scientific research, ecotourism, and climate resilience initiatives that benefit both biodiversity and local livelihoods.

A Step Towards Sustainable Conservation

The UNESCO designation of Spiti Valley as a Cold Desert Biosphere Reserve is more than symbolic; it presents opportunities for international collaborations, increased funding, and responsible eco-tourism frameworks that empower local communities.

Amitabh Gautam, Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (Wildlife), highlighted that this recognition will enhance India’s role in globally conserving fragile Himalayan habitats and building climate resilience. It also highlights the delicate balance required to promote development, tourism, and conservation simultaneously in high-altitude ecosystems.

This milestone underscores the significance of traditional ecological knowledge and community involvement in preserving such unique landscapes, while fostering sustainable practices that address the mounting climate challenges facing the Himalayas.

Conclusion and Future Outlook

The recognition of Spiti Valley as India’s first Cold Desert Biosphere Reserve signifies a major stride in environmentally conscious development and habitat preservation. It emphasizes the importance of protecting irreplaceable ecosystems while supporting local communities through sustainable initiatives.

As the world’s climate crises intensify, the successes and lessons learned from Spiti’s conservation model could serve as an inspiring blueprint for other fragile ecosystems globally.