Source: Catch News | Author: Ramakrishna Upadhya�| Image Courtesy:�livemint Times of India

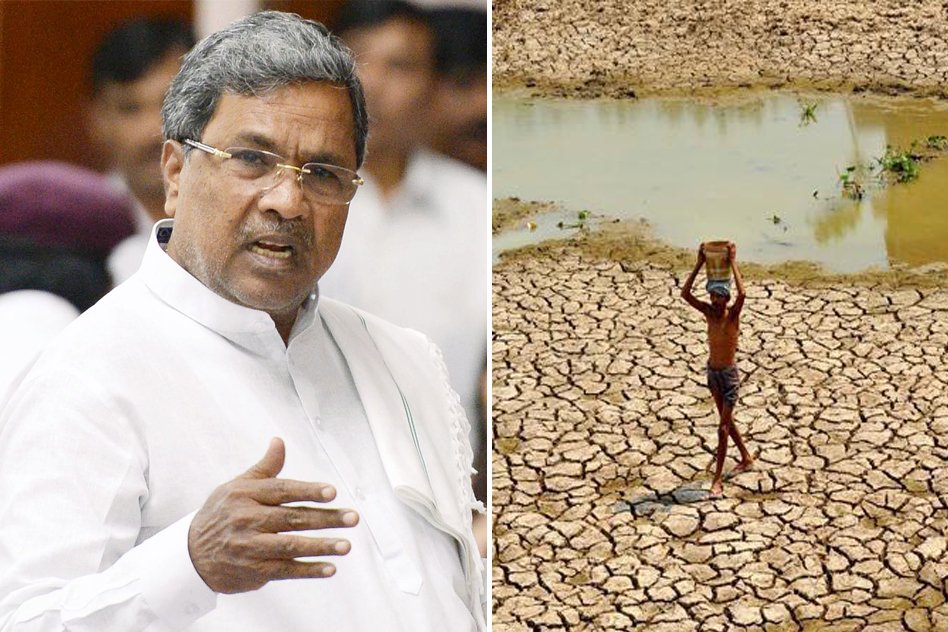

Chilling: How Siddaramaiah Slept While Drought Ravaged Karnataka

14 May 2016 8:32 PM GMT

Not many people would be able to answer this question correctly: which state has the most drought-affects districts in India after Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar?

None of these. It’s Karnataka.

The pity is that Karnataka has remained drought-prone for decades despite having over two dozen east and west flowing rivers, which empty most of their waters in the neighbouring states or the seas.

With the state now reeling under its worst drought in four decades, Chief Minister Siddaramaiah led an all party delegation to meet Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Delhi last week, with a begging bowl.

He was repeating what SM Krishna had done 15 years ago in 2001, when the state was suffering the third consecutive years of severe drought. Atal Bihari Vajpayee was the prime minister then.

The only difference between the two “missions” to New Delhi was in the scale of financial relief sought. The assistance sought from the Centre has reached such obscene proportions over these years, it’s difficult to explain with any rational argument.

While the Krishna regime had asked for Rs 904 crore for drought relief, and received Rs 29.36 crore from the Calamity Relief Fund as the first instalment, Siddaramaiah presented a memorandum requesting over Rs 12,000 crore in central aid.

The latter needs some elaboration. In his 40-page memorandum, the chief minister claimed that 27 of Karnataka‘s 30 districts were facing drought or drought-like conditions, which had caused crop losses of about Rs 15,636 crore. He also wanted money to help provide drinking water through tankers, arrange water and fodder for the cattle, and provide employment to people affected by the drought.

Just as he had done with Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Akhilesh Yadav, who had sought Rs 10,000 crore, Modi, along with his senior officials, listened to Siddaramaiah’s delegation for nearly 90 minutes, and promised help.

Considering that drought has become a recurring phenomenon in India, the Centre has already established the National Disaster Relief Fund to provide relief expeditiously. So, by the time Siddaramaiah met Modi, the Centre had already sanctioned Rs 1,540 crore relief for the kharif season and another Rs 723 crore for the rabi season.

Much of the blame, therefore, lies with the state government. Although ominous signs of a second consecutive drought were visible as early as September, Siddaramaiah’s regime failed to adequately prepare for it. And even as crops withered, water sources dried up and daily labourers began to migrate in search of work, the state machinery remained comatose until as late as April.

It was only after the newly-appointed state BJP president BS Yeddyurappa announced he would start touring drought-affected areas that Siddaramaiah woke from his slumber and hit the road. He constituted four sub-committees of ministers for four revenue divisions to supervise urgent relief works.

Then, as complaints of officials’ apathy poured in, Siddaramaiah suspended scores of tehsildars who had been found to be lax in discharging their duties. At the same time, the government tried to offer work, and food, to people through the MGNREGA wherever possible.

Of Karnataka’s 176 taluks, 136 taluks have been declared drought-hit. With most reservoirs, wells and lakes running dry, providing drinking water to the people and cattle became a major challenge. Irrigation canals were closed to save water for people and livestock. Most gram panchayats, especially in the worst-hit northern Karnataka, were struggling to supply 10-15 pots, or about 150 litres, of water to parched regions through tankers once in three days.

Not many people would be able to answer this question correctly: which state has the most drought-affects districts in India after Rajasthan? Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar?

None of these. It’s Karnataka.

The pity is that Karnataka has remained drought-prone for decades despite having over two dozen east and west flowing rivers, which empty most of their waters in the neighbouring states or the seas.

With the state now reeling under its worst drought in four decades, Chief Minister Siddaramaiah led an all party delegation to meet Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Delhi last week, with a begging bowl.

He was repeating what SM Krishna had done 15 years ago in 2001, when the state was suffering the third consecutive years of severe drought. Atal Bihari Vajpayee was the prime minister then.

The only difference between the two “missions” to New Delhi was in the scale of financial relief sought. The assistance sought from the Centre has reached such obscene proportions over these years, it’s difficult to explain with any rational argument.

While the Krishna regime had asked for Rs 904 crore for drought relief, and received Rs 29.36 crore from the Calamity Relief Fund as the first instalment, Siddaramaiah presented a memorandum requesting over Rs 12,000 crore in central aid.

The latter needs some elaboration. In his 40-page memorandum, the chief minister claimed that 27 of Karnataka’s 30 districts were facing drought or drought-like conditions, which had caused crop losses of about Rs 15,636 crore. He also wanted money to help provide drinking water through tankers, arrange water and fodder for the cattle, and provide employment to people affected by the drought.

Siddaramaiah pegs crop losses from drought at Rs 15,636 crore, seeks Rs 12,000 crore in central aid

Just as he had done with Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Akhilesh Yadav, who had sought Rs 10,000 crore, Modi, along with his senior officials, listened to Siddaramaiah’s delegation for nearly 90 minutes, and promised help.

Considering that drought has become a recurring phenomenon in India, the Centre has already established the National Disaster Relief Fund to provide relief expeditiously. So, by the time Siddaramaiah met Modi, the Centre had already sanctioned Rs 1,540 crore relief for the kharif season and another Rs 723 crore for the rabi season.

Much of the blame, therefore, lies with the state government. Although ominous signs of a second consecutive drought were visible as early as September, Siddaramaiah’s regime failed to adequately prepare for it. And even as crops withered, water sources dried up and daily labourers began to migrate in search of work, the state machinery remained comatose until as late as April.

It was only after the newly-appointed state BJP president BS Yeddyurappa announced he would start touring drought-affected areas that Siddaramaiah woke from his slumber and hit the road. He constituted four sub-committees of ministers for four revenue divisions to supervise urgent relief works.

Then, as complaints of officials’ apathy poured in, Siddaramaiah suspended scores of tehsildars who had been found to be lax in discharging their duties. At the same time, the government tried to offer work, and food, to people through the MGNREGA wherever possible.

Of Karnataka’s 176 taluks, 136 taluks have been declared drought-hit. With most reservoirs, wells and lakes running dry, providing drinking water to the people and cattle became a major challenge. Irrigation canals were closed to save water for people and livestock. Most gram panchayats, especially in the worst-hit northern Karnataka, were struggling to supply 10-15 pots, or about 150 litres, of water to parched regions through tankers once in three days.

Most gram panchayats in north Karnataka can’t supply 150 litres of water even once in three days

As the water level in the mighty Almatti reservoir, which has a capacity of 124 tmcft, fell alarmingly to less than 10% and touched dead storage limit, the government requested Maharashtra for an emergency supply of 2 tmcft water from Krishna river. The neighbouring state responded positively and quickly, though it was also battling drought in its territory.

In Karnataka’s 13 major reservoirs, the combined storage has sunk to under 18%. The 151-tmcft capacity Linganamakki now has 33 tmcft of water. The situation is equally grave in the case of Almatti (124 tmcft capacity, 17.12 tmcft left), Tungabhadra (100.86 tmcft; 2.20 tmcft), Krishnaraja Sagar Dam (49 tmcft; 10.67 tmcft). The authorities believe the reservoirs will barely last another two weeks.

Tamil Nadu, which has a long-running dispute with Karnataka over sharing of Kaveri river waters, has been quiet for a while as there is hardly any water in the KRS, Kabini and Hemavathy reservoirs, but the southern neighbour is bound to stake its claim once the monsoon begins.

If this wasn’t suffering enough, heatwave conditions have been reported from nearly everywhere, with the temperatures ranging between 40 and 45 degrees Celsius in half the state. Bengaluru, known for its salubrious climate, recently recorded 39 degrees Celsius continuously for a couple of weeks, breaking an 85-year-old record.

The root cause of rising temperatures and gradual desertification of the state, experts say, is the unbridled destruction of forests and felling of trees in urban areas.

According to the India State of Forests Report, 2015, Karnataka has added 289 sq km of forests in the past two years. This finding, however, conceals many facts: a single district, Tumakuru, accounts for this entire “increase” in the forest cover; and more crucially, the new survey includes all types of tree covers and plantations, which hides the destruction of genuine forests, especially in the Western Ghats.

In his book Everyone Loves A Good Drought, P Sainath recounts how droughts in this country only feed the greed of officials and politicians through massive corruption, and how policies to mitigate the calamities change little on the ground. Karnataka’s ongoing misery too shall pass, only for the whole charade of announcing schemes and begging for funds to play out all over again when the drought returns.

All section

All section